Privacy By Design: How To Sell Privacy And Make Change

Privacy By Design: How To Sell Privacy And Make Change

Joe Toscano2018-09-28T13:50:13+02:002018-09-28T21:41:47+00:00

Privacy is a fundamental human right that allows us to be our true selves. It’s what allows us to be weirdos without shame. It allows us to have dissenting opinions without consequence. And, ultimately, it’s what allows us to be free. This is why many nations have strict laws concerning privacy. However, in spite of this common understanding, privacy on the Internet is one of the least understood and poorly defined topics to date because it spans a vast array of issues, taking shape in many different forms, which makes it incredibly difficult to identify and discuss. However, I’d like to try to resolve this ambiguity.

In the United States, it is a federal offense to open someone’s mail. This is considered a criminal breach of privacy that could land someone in prison for up to five years. Metaphorically speaking, each piece of data we create on the Internet — whether photo, video, text, or something else — can be thought of as parcel of mail. However, unlike opening our mail in real life, Internet companies can legally open every piece of mail that gets delivered through their system without legal consequence. Moreover, they can make copies of it as well. What these companies are doing would be comparable to someone opening our mail, copying it at Kinkos, then storing it in a file cabinet with our name on it and sharing it with anyone willing to pay for it. Want to open that file cabinet or delete some of the copies? Too bad. Our mail is currently considered their property, and we have almost no control over how it gets used.

Could you imagine the outrage the public would experience if they found out that the postal service was holding their mail hostage and selling it to whoever was willing to pay? What’s happening with data on the Internet is no different, and it’s time this changes.

It’s more than just a matter of ethics that this happens, it’s a matter of basic human rights.

The problem with making the changes that need to be made (without changes being forced into place by regulation) is putting dollar signs to the issues. What is the financial return on a 20,000-hour engineering investment to improve consumer privacy standards? Are consumers demanding these changes? Because if it doesn’t make a fiscal return and consumers aren’t demanding it, then why should change be made? And even if they are and there is a return, what does 20,000 hours of investment even look like? What is going to be put on the product roadmap and when? These are all valid concerns that need to be addressed in order to help us move forward effectively. So, let’s discuss.

Recommended reading: Using Ethics In Web Design

Do Consumers Want It?

The answer to this question is a hard yes. Findings by Pew Research Center show that 90 percent of adults in the United States believe it is important that they have control over what information is collected about them, 93 percent believe it’s important they can control who has access to this information, and 86 percent have taken steps to remove or mask their digital footprints. Similar numbers were discovered about Europeans in doteveryone’s 2018 Digital Attitudes report. Despite these numbers, 59 percent still feel like it is impossible to remain anonymous online, 68 percent believe current laws do not do enough to protect their privacy, and only 6 percent are “very confident” that government agencies can keep them secure.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. This is consumer demand, and until those consumers start leaving old products behind, there’s no fiscal reason to make any change. And (although I don’t agree with your logic) you’re right. Right now there is little fiscal reason to make any change. However, when consumer demand reaches a critical mass, things always change. And the businesses that lead the way before the change is demanded always win in the long run. Those who refuse to make a change until they’re forced to always feel the most pain. History shows this to be the truth. But what’s going to happen in legislation that will change business so much? Great question.

What’s about to happen to data protection and privacy standards across the world, through regulation, will not be so different than what occurred less than a decade ago when consumers demanded protection from spam emails, which resulted in the CAN-SPAM Act in the United States — but on a much greater scale, and with exponentially greater impact. This legislation, which was created because consumers were sick of getting spam emails, set the rules for commercial email, established requirements for commercial messages, gave recipients the right to have individuals and companies stop emailing them, and spelt out tough penalties for violations. As we enter a period where consumers are beginning to understand just how badly they’ve been deceived (for years, giving people intimate control of their data will undoubtedly be the future of data collection) — whether that be through free will or legislation. And those who choose to move first will win. Don’t believe me?

Consider the fact that engineers can get in legal trouble for the code they write. Apple Watch, Alexa, and FitBit data, among others have been used as evidence in court, changing consumer perception of their data. Microsoft and the Supreme Court of the United States went to court earlier this year to define where physical borders extend in cloud-based criminal activity, the beginning of what will be a long fight. These examples are just a peek into what’s coming. The people are demanding more, and we’re reaching the tipping point.

The first to take steps to respond to this demand is the EU, which established the GDPR, and now policymakers in other countries are beginning to follow suit, working on laws in their country to define our cyber future. For example, United States Senate Intelligence Committee Vice Chairman, Mark Warner recently laid out some of ideas in a summary report just a couple months ago, demonstrating where legislation may soon be headed in the States. But it’s not just the progressives who believe this to be the future; even right-wing influencers like Steve Bannon think we need regulation.

What we’re seeing is a human reaction to incredible manipulation. No matter how domesticated we may be compared to previous generations, people will always push back when they feel they’re being threatened. It’s a natural reaction that has allowed us to survive for millennia. Today, tech has become more than just a consumer-facing industry. It is now also becoming a matter of national security. And for this reason, there will be a reaction whether we like it or not. And it will be better if we come out with a strategy to prepare instead of getting swept under the rug. So, what’s the financial return you ask? Well, how much is your business worth? That’s how much.

Recommended reading: How GDPR Will Change The Way You Develop

For a simple framework of what exactly needs to be addressed and why, we can hold several truths to be foundational in the creation of digital systems:

- Privacy must be proactive, not reactive, and must anticipate privacy issues before they reach the user.

These issues are not issues that we want to deal with after a problem has come to life but are instead issues we want to prevent entirely, if possible.? - Privacy must be the default setting.

There is no “best for business” option in regards to privacy; this is an issue that is about what’s best for the consumer, which, in the long run, will be better for the business. We can see what happens when coercive flaws are exposed to the public through what happened to Paypal and Venmo in August 2018 when Public by Default was released to the public, bringing a smattering of bad press to the brand. More of this is sure to come to the businesses that wait for something bad to happen before making a change.? - Privacy must be positive sum and should avoid dichotomies.

There is no binary relationship to be had with privacy; it is a forever malleable issue that needs constant oversight and perpetual iteration. Our work doesn’t end at the terms and service agreement, it lasts forever, and should be considered a foundational element of your product that evolves with the product and enables consumers to protect themselves — not one that takes advantage of their lack of understanding.? - Privacy standards must be visible, transparent, open, documented and independently verifiable.

There’s no great way to define a litmus test for your privacy standards, but a couple of questions we should all ask ourselves as business people are: First, if the press published your privacy agreement, would it be understandable? Second, if it were understandable, would consumers enjoy what they read? And last but not least, if not, what do you need to change??

These principles will be highly valuable foundations to keep in mind as products are built and evolve. They represent quick and easy questions to ask yourself and your team that will allow you to have a good baseline of ethics, but for a lengthier piece on legal foundations you can read more from Heather Burns, who outlined several additional principles last year on Smashing. And for a full list of things to inspect during a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA), you can also check out how assessments are done according to:

- The United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO)

- The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

- The United States Department of Homeland Security

But before rushing off to make changes in your product, first let’s point out some of the current flaws out in the wild and talk about what change might look like once they are implemented properly.

How To Make Change

One of the biggest problems with US privacy practices is how hard it is to understand terms and service agreements (T&S), which play a major role in defining privacy but tend to do so very poorly. Currently, users are forced to read long documents full of legal language and technical jargon if they hope to understand what they’re agreeing to. One study actually demonstrated that it would take approximately 201 hours (nearly ten days) per year for the average person to read every privacy policy they encounter on an annual basis. The researchers estimated that the value of this lost time would amount to nearly $781 billion per year, which is beyond unacceptable considering these are the rules that are supposed to protect consumers — rules that are touted to be easy and digestible. This puts consumers in a position where they’re forced to opt-in without truly understanding what they’re getting into. And in many cases it’s not even the legal language that’s coercive, it’s the way options are given, in general, as clearly proven across various experiences:

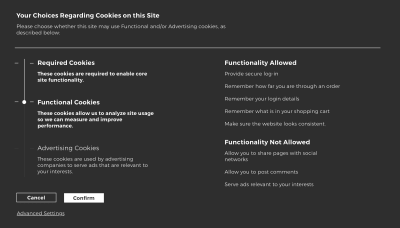

The example given above is generic wireframe, but I chose to do this because we’ve all seen patterns like this and others like it that are related to collecting more specific types of data. I could list specific examples, but the list would go on forever and there’s no reason to list off specific companies demonstrating manipulative patterns because these patterns (and other, very similar patterns) can be found on nearly every single website or app on the Internet. There’s one major problem with asking for consent this way: Consumers aren’t allowed to not accept terms and services without several extra steps, lots of reading, and often much more. This is a fundamental flaw that needs to be addressed because asking for consent means there needs to be an option to say no, and in order to know whether “no” is the best option, consumers need to understand what they’re consenting to. However, products aren’t built that way. Why? Well, it’s best for business.

If we really sit and think about this, what’s easy to see but let go unrecognized is that companies spend more time creating splash pages to explain how to use the app than we do to explain what data is being collected and why. Why? Simple changes to the way T&S agreements are made would not only make consumers more aware of what they’re signing up for, but also allow them to be more responsible consumers. We can see some of these changes already being made due to the impact the GDPR has been having across the world. In many European nations, it is not uncommon for consent to be asked through modals like these:

This first example is a good step forward. It tells the consumer what their data will be used for, but it’s still lacking transparency about where the data will be going and giving priority to the agreement without an option to decline. It also jams everything into a single body of text, which makes the information much less digestible.

A better example of how this might be designed is something like the modal below, which is now common among many European sites:

This gives consumers a comprehensive understanding of what their data will be used for and does it in a digestible manner. However, it still lacks any significant information about where the data will be going after they consent. There’s not a single clue as to where their data will be shared, who it will be shared with, and what limitations exist within those agreements. While this is much better than the majority of options on the web, there are still improvements to be made.

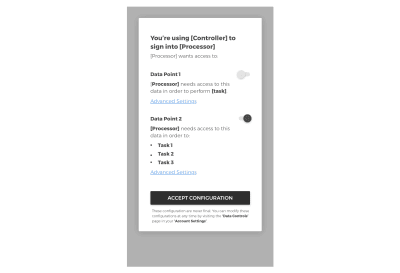

Third-Party Login Prompt

For example, when using a third-party service to log into your platform, consumers should be made well aware of the following:

- What data is going to be taken from the third-party;

- What it’s being used for and how it might affect their experience if you don’t have access to it;

- Who else has or might have access to it.

To implement this in a way that gives the consumer control, this experience should also allow consumers to opt-in to individual parts of the collection, not be forced to agree to everything or nothing at all.

This would make the T&S digestible and allow consumers to opt into what they truly agree to, not what the company wants them to agree to. And to make sure it’s truly opt-in, the default should be set to opt-out. This would be a small change that would make a dramatic difference in the way consent is asked for. Today, most companies blanket this content in legal jargon to hide what they’re really interested in, but the days of asking for consent in this way are quickly coming to an end.

If you’re providing consumers with a meaningful service, and doing so ethically, these changes shouldn’t be an issue. If there is a true value to the service, consumers are not going to resist your ask. They just want to know who they can and cannot trust, and this is one simple step that can help your business prove its trustworthiness.

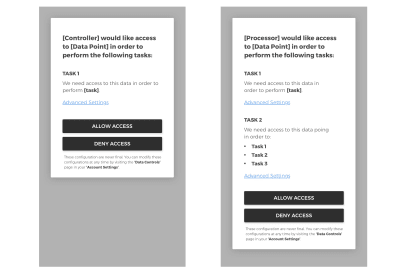

Single- And Multi-Point Data Collection Requests

Next, when it comes to creating understandable T&S agreements for your platform, we have to consider how this might play out more contextually — within the application experience. Keep in mind that if it’s all given up front, that’s not digestible. For this reason, data collection request should happen contextually, when the consumer is about to use part of your service that requires an extra layer of data to be collected.

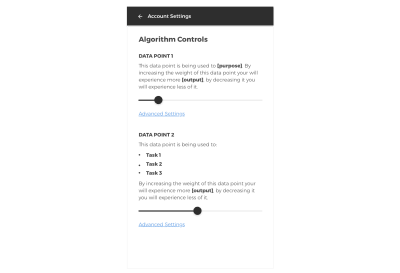

To demonstrate how this ask may occur, here are a couple of examples of what a single- and multi-point data collection request might look like:

Breaking the T&S down into digestible interaction points within the experience instead of asking the user for everything up front allows them to get a better understanding of what’s going on and why. If you don’t need the data to improve the experience, why is it being collected? And if it’s being collected for frivolous reasons that only benefit the company, then be honest. That’s just basic honesty, which unfortunately is considered revolutionary, progressive customer service in the modern world.

The biggest key to these initial asks is that none of this should be opt-in by default. All initial triggers should give the people using the tool to opt-in if they choose and use it without opting in if they choose. The days of forced opt-in (or, worse yet, coercive opt-in) are coming to an abrupt halt, and those who lead the way will stay ahead of the pack for a long time to come.

Data Control Center

Beyond asking for consent in a meaningful way, it will also be important that we give consumers the ability to control their data post-hoc. Consumers’ access to control their data should not end at the terms and service agreement. Somewhere in their account controls, there should also be a place (or places) where consumers can control their data on the platform after they’ve invested time with the service. This area should show them what data is being collected, who it’s being shared with, how they can remove it, and much more.

The idea of full data control may seem incredibly liberal, but it is no doubt the future. And as the property of the consumer creating the data, it should be considered a basic human right. There’s no reason why this should be a debate at this point in history. Data represents the story of our lives — collectively — and combined it creates vast amounts of power against those who create it, especially if we allow the systems to remain black boxes. So, beyond giving consumers access to their data, as we’ve discussed in the previous sections, we’ll also need to make the experience more understandable so that consumers can defend themselves.

Create Explainable AI

While it is incredible to get a suggested result that shows us things we want before we even knew we wanted them, this also puts machines in a powerful position they are not yet ready to uphold alone. When machines are positioned as experts and perform at a level that is intelligent enough to pass as such, the public will generally trust them until they fail. However, if machines fail in ways the public is incapable of understanding, they will remain expert despite their failure, which is one of the greatest threats to humanity.

For example, if someone were to use a visual search tool to identify the difference between an edible mushroom and a poisonous mushroom, and they didn’t know that the machine told them a poisonous mushroom was safe, that person could die. Or what happens when a machine determines the outcome of a court case and isn’t required to provide an explanation for its decision? Or worse yet, what about when these technologies are used for military purposes and are given the right to use lethal force? That last situation might sound extreme, but it is an issue that is currently being debated within the United Nations.

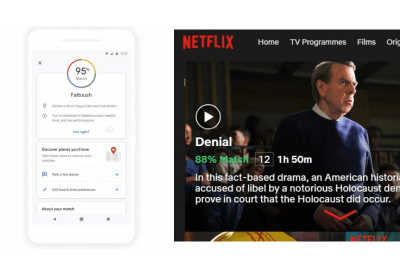

To ensure the public is capable of understanding what’s happening behind the scenes we need to create what DARPA calls explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) — tools that explain how machines make their decisions and the accuracy with which these tasks have been achieved. This isn’t about giving trade secrets away but allowing consumers to feel like they can trust these machines and defend themselves if an error were to occur.

Although it is not based in artificial intelligence, a good example of what this might look like is CreditKarma, which allows people to have a better understanding of their credit score — a system that used to be hidden just like algorithms are today. This tool allows consumers to have a better understanding of what’s happening behind the scenes and debate the legitimacy of their results if they believe the system has failed. Similar tools are being created with systems like Google’s Match score on Maps and Netflix Percent Match on shows but these systems are just beginning to scratch the surface of explainable AI.

Despite these efforts, most algorithms today dictate our experience based on what a company thinks we want. But consumers should no longer be invisibly controlled by large, publicly traded corporations. Consumers should have the right to control their own algorithm. This could be something as simple as letting them know what variables are used for what parts of the experience and how changing the weights of each variable will impact their experience, then giving them the ability to tweak that until it fits their needs — including turning the algorithm off completely, if that’s what they prefer. Whether this would be a paid feature or a free feature is still up for debate, but what is not debatable is whether this freedom should be offered.

While the example above is a generic proposal, it begins to imagine how we might make the experience in more specific situations. By giving consumers the ability to understand their data, the way it’s being used, and how that affects their lives, we will have designed a system that puts consumers in control of their own freedom.

However, no matter how well these changes are made, we must also realize that giving people better control of their privacy does not automatically imply a safer environment for consumers. In fact, it may make things worse. Studies have shown that giving people better control of their data actually makes it more likely that they’ll provide more sensitive information. And if the consumer is unaware of how that data may be used (even if they know where it’s being shared), this puts them in harm’s way. In this sense, giving consumers better control of their data and expecting it to make the Internet safer is like putting a nutrition label on a Snickers and expecting it to make the candy bar less fattening. It won’t, and people are still going to eat it.

While I do believe that consumers have a fundamental right to better privacy controls and greater transparency, I also believe it is our job, as data-literate technologists to not only build better systems but also to help the public understand Internet safety. So, the last step in bringing this together is to bring awareness to the fact that control isn’t all consumers need. They also need to understand what is happening on the backend — and why. This doesn’t necessarily mean providing them with source code or giving away their IPs, but at least providing them with enough information to understand what’s going on at a base level, as a matter of safety. And in order to achieve this, we’ll need to push beyond our screens. We’ll need to extend our work into our communities and help create that future.

Recommended reading: Designing Ethics: Shifting Ethical Understanding In Design

Incentivize Change

Giving up privacy is something the population has been corralled into due to the monopolies that exist in the tech world, consumers’ misunderstanding of why this is so dangerous within, and a lack of tactical solutions associated with fiscal returns. However, this is a problem that needs to be solved. As Barack Obama noted in his administration’s summary of concerns about internet privacy:

“One thing should be clear: Even though we live in a world in which we share personal information more freely than in the past, we must reject the conclusion that privacy is an outmoded value. It has been at the heart of our democracy from its inception, and we need it now more than ever.”

Creating trustworthy and secure data-sharing experiences will be one of the biggest challenges our world will face in the coming decades.

We can look at how Facebook’s stock dropped 19 percent in one day after announcing they’re going to re-focus on privacy efforts as proof of how difficult making these changes may be. This is because investors who have recently been focused on the short-term revenue growth know how badly companies need to implement better strategies, but also realize the cost involved if the public starts to question a business — and Facebook’s public statement admitting this startled the sheep.

While the process will not be easy (and at many times may be painful), we all know that privacy is the soft underbelly of tech and it’s time to change that. The decisions being made today will pay off big in the long run; a stark difference to the short-term, quarterly mindset that has come to dominate business in the past decade or so of growth. Thus, discovering creative ways to make these issues a priority for all stakeholders should be considered essential for businesses and policymakers alike, which means our job as technologists needs to extend beyond the boardroom.

For example, a great way to incentivize these changes beyond discussing the numbers and issues brought up in this article would be through tax breaks for companies that allocate large amounts of their budget to improving their systems. Breaks could be given to companies that decide to supply regular training or workshops for their staff to help make privacy and security a priority in the company culture. They could be given to companies that hire professional hackers to find loopholes in their systems before attacks occur. They could be given to those who allocate large amounts of hours to restructuring their business practices in a way that benefits consumers. In this sense, such incentives would not be so different than tax breaks given to businesses that implement eco-friendly practices.

The idea of tax breaks may sound outrageous to some, but incentives such as these would represent a more proactive solution than the way things are handled now. While it may feel good to read a headline stating “Google fined a record $5 billion by the EU for Android antitrust violations,“ we must keep in mind that fines like this only represent a small fraction of such companies’ revenue. Combine this with the fact that most cases take several years or decades to conclude, and that percentage only gets smaller. With this for consideration, the idea of tax breaks can be approached from a different perspective, which is that they are not about rewarding previously negligent behavior but about increasing public safety in a way that is in the best interest of everyone involved. Maintaining our current system, which allows companies to string out court cases while they continue their malpractices is just as, if not more, dangerous than having no laws at all.

If you enjoyed reading this article and think others should read it as well, please help spread the word.

This article is the beginning of a series of articles I will be writing about dedicated to Internet safety, in which I will work to put fiscal numbers to ethical design patterns so that we, as technologists can change the businesses we’re building and create a better culture surrounding the development of internet-connected experiences.

(il, ra, yk)

(il, ra, yk)