An Introduction To WebBluetooth

An Introduction To WebBluetooth

Niels Leenheer2019-02-13T13:00:51+01:002019-02-13T20:05:50+00:00

With Progressive Web Apps, the web has been ever more closely moving towards native apps. However, with the added benefits that are inherent to the web such as privacy and cross-platform compatibility.

The web has traditionally been fantastic about talking to servers on the network, and to servers on the Internet specifically. Now that the web is moving towards applications, we also need the same capabilities that native apps have.

The amount of new specifications and features that have been implemented in the last few years in browsers is staggering. We’ve got specifications for dealing with 3D such as WebGL and the upcoming WebGPU. We can stream and generate audio, watch videos and use the webcam as an input device. We can also run code at almost native speeds using WebAssembly. Moreover, despite initially being a network-only medium, the web has moved towards offline support with service workers.

That is great and all, but one area has been almost the exclusive domain for native apps: communicating with devices. That is a problem we’ve been trying to solve for a long time, and it is something that everybody has probably encountered at one point. The web is excellent for talking to servers, but not for talking to devices. Think about, for example, trying to set up a router in your network. Chances are you had to enter an IP address and use a web interface over a plain HTTP connection without any security whatsoever. That is just a poor experience and bad security. On top of that, how do you know what the right IP address is?

HTTP is also the first problem we run into when we try to create a Progressive Web App that tries to talk to a device. PWAs are HTTPS only, and local devices are always just HTTP. You need a certificate for HTTPS, and in order to get a certificate, you need a publicly available server with a domain name (I’m talking about devices on our local network that is out of reach).

So for many devices, you need native apps to set the devices up and use them because native apps are not bound to the limitations of the web platform and can offer a pleasant experience for its users. However, I do not want to download a 500 MB app to do that. Maybe the device you have is already a few years old, and the app was never updated to run on your new phone. Perhaps you want to use a desktop or laptop computer, and the manufacturer only built a mobile app. Also not an ideal experience.

WebBluetooth is a new specification that has been implemented in Chrome and Samsung Internet that allows us to communicate directly to Bluetooth Low Energy devices from the browser. Progressive Web Apps in combination with WebBluetooth offer the security and convenience of a web application with the power to directly talk to devices.

Bluetooth has a pretty bad name due to limited range, bad audio quality, and pairing problems. But, pretty much all those problems are a thing of the past. Bluetooth Low Energy is a modern specification that has little to do with the old Bluetooth specifications, apart from using the same frequency spectrum. More than 10 million devices ship with Bluetooth support every single day. That includes computers and phones, but also a variety of devices like heart rate and glucose monitors, IoT devices like light bulbs and toys like remote controllable cars and drones.

Recommended reading: Understanding API-Based Platforms: A Guide For Product Managers

The Boring Theoretical Part

Since Bluetooth itself is not a web technology, it uses some vocabulary that may seem unfamiliar to us. So let’s go over how Bluetooth works and some of the terminology.

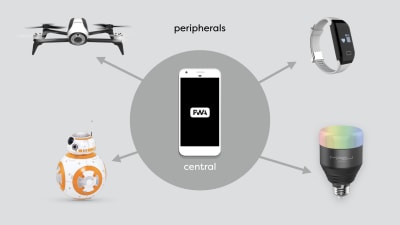

Every Bluetooth device is either a ‘Central device’ or a ‘Peripheral’. Only central devices can initiate communication and can only talk to peripherals. An example of a central device would be a computer or a mobile phone.

A peripheral cannot initiate communication and can only talk to a central device. Furthermore, a peripheral can only talk to one central device at the same time. A peripheral cannot talk to another peripheral.

A central device can talk to multiple peripherals at the same time and could relay messages if it wanted to. So a heart rate monitor could not talk to your lightbulbs, however, you could write a program that runs on a central device that receives your heart rate and turns the lights red if the heart rate gets above a certain threshold.

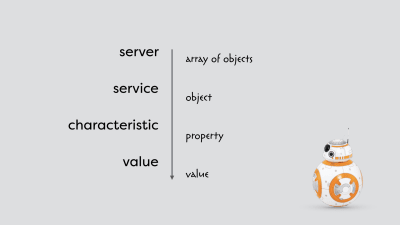

When we talk about WebBluetooth, we are talking about a specific part of the Bluetooth specification called Generic Attribute Profile, which has the very obvious abbreviation GATT. (Apparently, GAP was already taken.)

In the context of GATT, we are no longer talking about central devices and peripherals, but clients and servers. Your light bulbs are servers. That may seem counter-intuitive, but it actually makes sense if you think about it. The light bulb offers a service, i.e. light. Just like when the browser connects to a server on the Internet, your phone or computer is a client that connects to the GATT server in the light bulb.

Each server offers one or more services. Some of those services are officially part of the standard, but you can also define your own. In the case of the heart rate monitor, there is an official service defined in the specification. In case of the light bulb, there is not, and pretty much every manufacturer tries to re-invent the wheel. Every service has one or more characteristics. Each characteristic has a value that can be read or written. For now, it would be best to think of it as an array of objects, with each object having properties that have values.

Unlike properties of objects, the services and characteristics are not identified by a string. Each service and characteristic has a unique UUID which can be 16 or 128 bits long. Officially, the 16 bit UUID is reserved for official standards, but pretty much nobody follows that rule.

Finally, every value is an array of bytes. There are no fancy data types in Bluetooth.

A Closer Look At A Bluetooth Light Bulb

So let’s look at an actual Bluetooth device: a Mipow Playbulb Sphere. You can use an app like BLE Scanner, or nRF Connect to connect to the device and see all the services and characteristics. In this case, I am using the BLE Scanner app for iOS.

The first thing you see when you connect to the light bulb is a list of services. There are some standardized ones like the device information service and the battery service. But there are also some custom services. I am particularly interested in the service with the 16 bit UUID of 0xff0f. If you open this service, you can see a long list of characteristics. I have no idea what most of these characteristics do, as they are only identified by a UUID and because they are unfortunately a part of a custom service; they are not standardized, and the manufacturer did not provide any documentation.

The first characteristic with the UUID of 0xfffc seems particularly interesting. It has a value of four bytes. If we change the value of these bytes from 0x00000000 to 0x00ff0000, the light bulb turns red. Changing it to 0x0000ff00 turns the light bulb green, and 0x000000ff blue. These are RGB colors and correspond exactly to the hex colors we use in HTML and CSS.

What does that first byte do? Well, if we change the value to 0xff000000, the lightbulb turns white. The lightbulb contains four different LEDs, and by changing the value of each of the four bytes, we can create every single color we want.

The WebBluetooth API

It is fantastic that we can use a native app to change the color of a light bulb, but how do we do this from the browser? It turns out that with the knowledge about Bluetooth and GATT we just learned, this is relatively simple thanks to the WebBluetooth API. It only takes a couple of lines of JavaScript to change the color of a light bulb.

Let’s go over the WebBluetooth API.

Connecting To A Device

The first thing we need to do is to connect from the browser to the device. We call the function navigator.bluetooth.requestDevice() and provide the function with a configuration object. That object contains information about which device we want to use and which services should be available to our API.

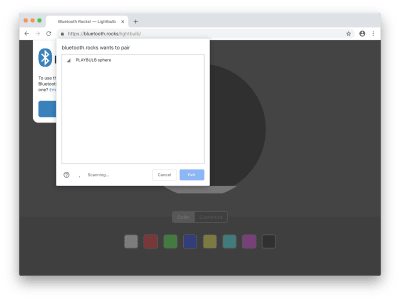

In the following example, we are filtering on the name of the device, as we only want to see devices that contain the prefix PLAYBULB in the name. We are also specifying 0xff0f as a service we want to use. Since the requestDevice() function returns a promise, we can await the result.

let device = await navigator.bluetooth.requestDevice({

filters: [

{ namePrefix: 'PLAYBULB' }

],

optionalServices: [ 0xff0f ]

});

When we call this function, a window pops up with the list of devices that conform to the filters we’ve specified. Now we have to select the device we want to connect to manually. That is an essential step for security and privacy and gives control to the user. The user decides whether the web app is allowed to connect, and of course, to which device it is allowed to connect. The web app cannot get a list of devices or connect without the user manually selecting a device.

After we get access to the device, we can connect to the GATT server by calling the connect() function on the gatt property of the device and await the result.

let server = await device.gatt.connect();

Once we have the server, we can call getPrimaryService() on the server with the UUID of the service we want to use as a parameter and await the result.

let service = await server.getPrimaryService(0xff0f);

Then call getCharacteristic() on the service with the UUID of the characteristic as a parameter and again await the result.

We now have our characteristics which we can use to write and read data:

let characteristic = await service.getCharacteristic(0xfffc);

Writing Data

To write data, we can call the function writeValue() on the characteristic with the value we want to write as an ArrayBuffer, which is a storage method for binary data. The reason we cannot use a regular array is that regular arrays can contain data of various types and can even have empty holes.

Since we cannot create or modify an ArrayBuffer directly, we are using a ‘typed array’ instead. Every element of a typed array is always the same type, and it does not have any holes. In our case, we are going to use a Uint8Array, which is unsigned so it cannot contain any negative numbers; an integer, so it cannot contain fractions; and it is 8 bits and can contain only values from 0 to 255. In other words: an array of bytes.

characteristic.writeValue(

new Uint8Array([ 0, r, g, b ])

);

We already know how this particular light bulb works. We have to provide four bytes, one for each LED. Each byte has a value between 0 and 255, and in this case, we only want to use the red, green and blue LEDs, so we leave the white LED off, by using the value 0.

Reading Data

To read the current color of the light bulb, we can use the readValue() function and await the result.

let value = await characteristic.readValue();

let r = value.getUint8(1);

let g = value.getUint8(2);

let b = value.getUint8(3);

The value we get back is a DataView of an ArrayBuffer, and it offers a way to get the data out of the ArrayBuffer. In our case, we can use the getUint8() function with an index as a parameter to pull out the individual bytes from the array.

Getting Notified Of Changes

Finally, there is also a way to get notified when the value of a device changes. That isn’t really useful for a lightbulb, but for our heart rate monitor we have constantly changing values, and we don’t want to poll the current value manually every single second.

characteristic.addEventListener(

'characteristicvaluechanged', e => {

let r = e.target.value.getUint8(1);

let g = e.target.value.getUint8(2);

let b = e.target.value.getUint8(3);

}

);

characteristic.startNotifications();

To get a callback whenever a value changes, we have to call the addEventListener() function on the characteristic with the parameter characteristicvaluechanged and a callback function.

Whenever the value changes, the callback function will be called with an event object as a parameter, and we can get the data from the value property of the target of the event. And, finally extract the individual bytes again from the DataView of the ArrayBuffer.

Because the bandwidth on the Bluetooth network is limited, we have to manually start this notification mechanism by calling startNotifications() on the characteristic. Otherwise, the network is going to be flooded by unnecessary data. Furthermore, because these devices typically use a battery, every single byte that we do not have to send will definitively improve the battery life of the device because the internal radio does not need to be turned on as often.

Conclusion

We’ve now gone over 90% of the WebBluetooth API. With just a few function calls and sending 4 bytes, you can create a web app that controls the colors of your light bulbs. If you add a few more lines, you can even control a toy car or fly a drone. With more and more Bluetooth devices making their way on to the market, the possibilities are endless.

Further Resources

- Bluetooth.rocks! Demos | (Source code on GitHub)

- “Web Bluetooth Specification,” Web Bluetooth Community Group

- Open GATT Registry

An unofficial collection of documentation for Generic Attribute services for Bluetooth Low Energy devices.

(dm, ra, il)

(dm, ra, il)