The Mythical Mythical Man-Month

The Mythical Mythical Man-Month

John Foreman2020-01-15T13:00:00+00:002020-01-16T11:00:07+00:00

As a product leader at a tech company, I am a bottomless pit of need. My job as the Chief Product Officer at Mailchimp is to bring the product to market that’s going to win in a very competitive space. Mailchimp’s aspirations are high, and to realize them we need to deliver a substantial amount of product to the market. Oftentimes to many at the company, it feels like we are doing too much. We’re always at the edge of the wheels coming off.

And when you’re doing too much and you decide to do more than even that, you will inevitably begin to hear The Mythical Man-Month referenced. It’s like one of those stress-relief balls where if you squeeze one end, then out pops the Mythical Man-Month at the other end.

Published by Frederick Brooks back in 1975 (you remember 1975, right? When software development 100% resembled software development in 2020?), this book is rather famous amongst software engineers. Specifically, there’s one point in the entire book that’s famous (I’m not convinced people read anything but this point if they’ve read the book at all):

“…adding more men lengthens, not shortens, the schedule.”

Easy fix. I’ll just staff women to projects from now on (see the Return of the King and the fight against the Witch King of Angmar).

But let’s assume that Brooks’ point holds regardless of the gender identification of the software engineers in question. Here’s the point: software is difficult to build with lots of complex interdependencies. And everyone needs to work together to get it done.

As I add people to a team, they need to be onboarded and grafted into the project. Someone’s gotta carve off the right work for them. The team has to communicate to make sure their stuff all works together, and each additional person increases that communication complexity geometrically. And at some point, adding people becomes a burden to the project — not a benefit.

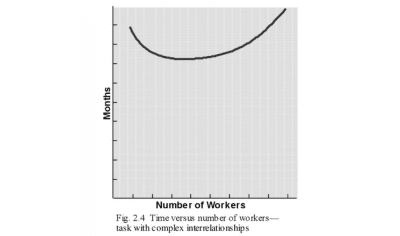

Here’s the graph from the book illustrating that point:

This is absolutely a fair point. That’s why I hear it so much at work. Exhausted individual contributors and exhausted leaders alike will toss it out — we can’t go faster, we can’t do more, stop the hiring, read The Mythical Man-Month and despair! The only solution is apparently to stop growing and kill some projects.

When I as CPO say, “we’re going to do this thing!” the reply then is often, “OK, so then what are we going to kill?” The Mythical Man-Month turns product development into a zero-sum game. If we want one thing, we must stop another. Now, that’s an actual myth, and I call hogwash.

And taken to its pathologically misinterpreted (we’ll get to this) conclusion, the book apparently says that the fastest tech company is one that employs all of four people — four men, apparently. Anything more just slows it all down. Someone should send Amazon, Apple, and Google copies of the book, so they can fix their obviously bloated orgs.

The only problem with this approach is that in a space where the competition is growing and iterating and executing — merely tamping organizational growth — editing and focusing the workload to match can be a recipe for extinction. You’ll be more sane and less stressed — right until you’re out of a job.

And as the owner of product management for my company, I’m not unsympathetic with this need to slow down and focus. We must ruthlessly prioritize! No doubt. But running a product is an exercise in contradiction. I must prioritize what I’ve got while simultaneously scheming to get more done. But what am I to do in the face of the Mythical Man-Month?

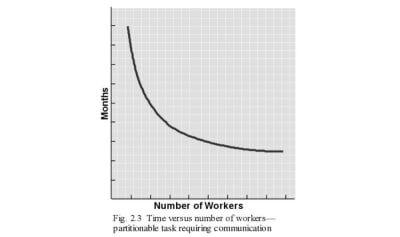

Surprisingly, the answer to this question comes from Brooks’ same book. Here’s another graph in the same chapter:

There is a battle in scaling product development. If the work you’re trying to accomplish is purely partitionable, then go ahead and add people! If your work is all connected, then at some point adding people is just wrong.

If someone says that I absolutely have to kill a project in order to start another one, that’s just not the case. If the two projects require very little communication and coordination, then we can scale away.

This is why adding cores to a CPU can increase the experienced speed of your computer or phone up to a point — something engineers should know all about. Sure, adding cores won’t help me complete a complex single-threaded computation. But it may help me run a bunch of independent tasks.

The conflict for a product executive then between scaling and ruthless prioritization can be managed.

- You ruthlessly prioritize in places that are single-threaded (the backlog for a product team let’s say).

- You scale by adding more cores to handle independent work.

Very rarely, however, is anything fully-independent of all else at a company. At the bare minimum, your company is going to centralize supporting functions (global IT, legal, HR, etc.) leading to bottlenecks.

It’s All About Dependency Management

The job of a product executive then becomes not only creating a strategy, but executing in a way that maximizes value for the customer and the business by ensuring throughput and reducing interdependency risk as much as possible. “As much as possible” being key here. That way you can make the company look as much like the latter graph rather than the former. Interdependency is a disease with no cure, but its symptoms can be managed with many treatments.

One solution is to assemble a strategic direction for the company that minimizes or limits dependency through a carefully-selected portfolio of initiatives. The funny thing here is that many folks will push back on this. Let’s say I have two options, one where I can execute projects A, B, and C that have very little coordination (let’s say they impact different products), and another option with projects D1, D2, and D3 that have tons of interdependencies (let’s say they all impact the same product). It’s often the case that the Mythical Man-Month will be invoked against the former plan rather than the latter. Because on paper it looks like more.

Indeed, it’s less “focused.” But, it’s actually less difficult from a dependency perspective and hence fairs better with added personnel.

Keep in mind, I’m not saying to choose a bunch of work for the company that’s not related. Mailchimp will not be building a microwave oven anytime soon. All work should drive in the same long-term direction. This approach can increase customer experience risk (which we’ll discuss later) as well as the burden on global functions such as customer research. Keep an eye out for that.

Another treatment is to create a product and program management process that facilitates dependency coordination and communication where necessary without over-burdening teams with coordination if not required. Sometimes in attempting to manage coordination so we can do more we end up creating such onerous processes that we end up doing less. It’s a balance between doing too little coordination causing the pieces to not inter-operate and doing too much coordination causing the pieces to never get built because we’re all in stand-ups for eternity.

The contention in the Mythical Man-Month is that as you add folks to a software project, the communication needs to increase geometrically. For example, if you have 3 people on the project, that’s 3 lines of communication. But if you have 4, that’s 6 lines of communication. One extra person, in this case, leads to double the communication! Fun. (This is, of course, an over-simplification of communication on software development projects.)

Different people have different roles and hence receive different amounts of autonomy. Perhaps the project manager needs to communicate with everyone on the team. But does an engineer working on the API need to communicate with the product marketer? Or can the marketer just go through the product manager? A good process and meeting cadence can then eliminate unnecessary communication and meetings. The point is that Brooks’ intercommunication formula is an upper bound on coordination, not a death sentence.

Finally, use tools, principles, and frameworks combined with independent work over actual collaboration to combat interdependency symptoms. For example, if I can coordinate two teams’ key performance indicators (KPIs, i.e. measurements of success) to incentivize movement in more-or-less the same direction, then their independent work is more likely to end up “closer together” than if their KPIs incentivize orthogonal movement. This won’t ensure things fit together perfectly, only that the work I need to do to make them fit together in the future is less than it might otherwise be. Other examples might include using “even-over” statements, design systems, and automated testing.

So there’s a start. But interdependencies take on lots of forms beyond code. Let me give an example from Mailchimp.

Customer Experience Risk: The Hidden (But Acceptable?) Cost Of Firewalling Work

Since Mailchimp’s customer is often a small business owner who’s a marketing novice (and there are millions of small business owners turned marketers worldwide), we must deliver an experience that is seamless and immediately understandable end-to-end. We’re not afforded the luxury of assembling a Frankenstein’s monster of clouds via acquisition the way that enterprise players can. We can’t paper over poorly-integrated software with consultants and account managers.

As a consumer product (think Instagram or a Nintendo Switch or a Roomba), we have to be usable out of the box. For an all-in-one marketing platform meant to power your business, that’s hard! And that means each thing Mailchimp builds must be seamlessly connected from an experience perspective.

But, perfectly partitioning projects then introduces experience risk. It’s not that the code can’t be written independently. That can be achieved, but there’s still a risk that the products will look like they’ve been built by different teams, and that experience can be really damn confusing for the user. We bump up against Conway’s law — our customers can tell where one team’s work ends and the other team’s work begins.

So you try to connect everyone’s work together — not just on the back-end but on the front-end, too. In the ecosystem era, dominated by CX excellence from players like Apple, this has become almost table stakes in the consumer space. But this is a Mythical Man-Month nightmare, though not from an engineering perspective this time. It’s from a service design perspective. As we add more people to all of this “end-to-end” connected work, everything slows to a collaborative crawl.

Other than the third fix I noted above, using tools and frameworks rather than over-watchers and stage-gates, there is another release valve: make some deliberate customer experience trade-offs. Specifically, where are we comfortable releasing an experience that’s disconnected from the rest (i.e. that’s sub-par)? Accepting risk and moving forward is the product leader’s job. And so you use some criteria to sort it out (perhaps it’s not holding new, low-traffic areas of the app to the same experience standards as your “cash cows”), and make a decision (e.g. iteration and learning over polish on adjacent innovations). This, of course, extends beyond design.

“

I’ll caveat this by saying the software I build doesn’t kill anyone. I wouldn’t advocate this approach if I were building a medical device. But at a marketing software company, I can deliberately isolate teams knowing that I’ve increased the odds of incompatibility as a trade-off for scaling up personnel and moving faster.

I’m sad to admit that the Mythical Man-Month is a reality at my company, and I suspect at yours as well. But it’s manageable — that’s the bottom line. Parallelization and dependency mitigation offer us a way out that limits the near-mythical status of the Mythical Man-Month. So the next time the stark dichotomy is raised at your company (scale to go slower or give up your aspirations) remember that if you’re smart about how you line up the work, you can still grow big.

Don’t Forget About The Softer Side Of Scaling

Keep in mind that managing the Mythical Man-Month will not stop engineers from invoking it like dark magic. They’re invoking the principle not only because there’s some truth in it, but because scaling just sucks (always) from an emotional and cognitive perspective. If I think I’m paid to write code and solve customer problems, the last thing I wanna do is change up my routine and figure out how to work with new people and a larger team.

As you scale your company, remember to empathize with the pain of scaling and change. A team that adds even a single member becomes a whole new team from a trust and cultural perspective. People are tired of this change. That means that while you go about managing and mitigating the Mythical Man-Month, you’ll need to manage the emotions surrounding growth. That’s perhaps the most critical task of all.

Strong belief in the Mythical Man-Month by a team in and of itself can bring its conclusions into reality. It’s basically the equivalent of the belief in flying in Peter Pan. If the team believes that scaling will slow them and they don’t buy into the change, they will indeed slow down.

So as you work to manage dependencies and introduce tools to help scale, make sure you clearly communicate the why behind the practices. Get folks involved in selecting the work and processes that mitigate man-month issues, because when they’re part of the change and their outlook changes, suddenly scaling becomes at least culturally possible.