A Complete Guide to Links and Buttons

There is a lot to know about links and buttons in HTML. There is markup implementation and related attributes, styling best practices, things to avoid, and the even-more-nuanced cousins of the link: buttons and button-like inputs.

Let’s take a look at the whole world of links and buttons, and all the considerations at the HTML, CSS, JavaScript, design, and accessibility layers that come with them. There are plenty of pitfalls and bad practices to avoid along the way. By covering it, we’ll have a complete good UX implementation of both elements.

Quick rules of thumb on when to use each:

- Are you giving a user a way to go to another page or a different part of the same page? Use a link (

link) - Are you making a JavaScript-powered clickable action? Use a button (

) - Are you submitting a form? Use a submit input (

)

Links

Links are one of the most basic, yet deeply fundamental and foundational building blocks of the web. Click a link, and you move to another page or are moved to another place within the same page.

Table of Contents

HTML implementation

A basic link

<a href="https://css-tricks.com">CSS-Tricks</a>That’s a link to a “fully qualified” or “absolute” URL.

A relative link

You can link “relatively” as well:

<!-- Useful in navigation, but be careful in content that may travel elsewhere (e.g. RSS) -->

<a href="/pages/about.html">About</a>That can be useful, for example, in development where the domain name is likely to be different than the production site, but you still want to be able to click links. Relative URLs are most useful for things like navigation, but be careful of using them within content — like blog posts — where that content may be read off-site, like in an app or RSS feed.

A jump link

Links can also be “hash links” or “jump links” by starting with a #:

<a href="#section-2">Section Two</a>

<!-- will jump to... -->

<section id="section-2"></section>Clicking that link will “jump” (scroll) to the first element in the DOM with an ID that matches, like the section element above.

? Little trick: Using a hash link (e.g. #0) in development can be useful so you can click the link without being sent back to the top of the page like a click on a # link does. But careful, links that don’t link anywhere should never make it to production.

? Little trick: Jump-links can sometimes benefit from smooth scrolling to help people understand that the page is moving from one place to another.

It’s a fairly common UI/UX thing to see a “Back to top” link on sites, particularly where important navigational controls are at the top but there is quite a bit of content to scroll (or otherwise navigate) through. To create a jump link, link to the ID of an element that is at the top of the page where it makes sense to send focus back to.

<a href="#top-of-page">Back to Top</a>Jump links are sometimes also used to link to other anchor () elements that have no href attribute. Those are called “placeholder” links:

<a id="section-2"></a>

<h3>Section 2</h3>There are accessibility considerations of these, but overall they are acceptable.

Disabled links

A link without an href attribute is the only practical way to disable a link. Why disable a link? Perhaps it’s a link that only becomes active after logging in or signing up.

a:not[href] {

/* style a "disabled" link */

}When a link has no href, it has no role, no focusability, and no keyboard events. This is intentional.

Do you need the link to open in a new window or tab?

You can use the target attribute for that, but it is strongly discouraged.

<a href="https://css-tricks.com" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer">

CSS-Tricks

</a>The bit that makes it work is target="_blank", but note the extra rel attribute and values there which make it safer and faster.

Making links open in new tabs is a major UX discussion. We have a whole article about when to use it here. Summarized:

Don’t use it:

- Because you or your client prefer it personally.

- Because you’re trying to beef up your time on site metric.

- Because you’re distinguishing between internal and external links or content types.

- Because it’s your way out of dealing with infinite scroll trickiness.

Do use it:

- Because a user is doing something on the current page, like actively playing media or has unsaved work.

- You have some obscure technical reason where you are forced to (even then you’re still probably the rule, not the exception).

Need the link to trigger a download?

The download attribute on a link will instruct the browser to download the linked file rather than opening it within the current page/tab. It’s a nice UX touch.

<a href="/files/file.pdf" download>Download PDF</a>The rel attribute

This attribute is for the relationship of the link to the target.

The rel attribute is also commonly used on the element (which is not used for creating hyperlinks, but for things like including CSS and preloading). We’re not including rel values for the element here, just anchor links.

Here are some basic examples:

<a href="/page/3" rel="next">Next</a>

<a href="/page/1" rel="prev">Previous</a>

<a href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/" rel="license">cc by 2.0</a>

<a href="/topics/" rel="directory">All Topics</a>rel="alternate": Alternate version of the document.rel="author": Author of the document.rel="help": A resource for help with the document.rel="license": License and legal information.rel="manifest": Web App Manifest document.rel="next": Next document in the series.rel="prev": Previous document in the series.rel="search": A document meant to perform a search in the current document.

There are also some rel attributes specifically to inform search engines:

rel="sponsored": Mark links that are advertisements or paid placements (commonly called paid links) as sponsored.rel="ugc": For not-particularly-trusted user-generated content, like comments and forum posts.rel="nofollow": Tell the search engine to ignore this and not associate this site with where this links to.

And also some rel attributes that are most security-focused:

rel="noopener": Prevent a new tab from using the JavaScriptwindow.openerfeature, which could potentially access the page containing the link (your site) to perform malicious things, like stealing information or sharing infected code. Using this withtarget="_blank"is often a good idea.rel="noreferrer": Prevent other sites or tracking services (e.g. Google Analytics) from identifying your page as the source of clicked link.

You can use multiple space-separated values if you need to (e.g. rel="noopener noreferrer")

And finally, some rel attributes come from the microformats standard, like:

rel="directory": Indicates that the destination of the hyperlink is a directory listing containing an entry for the current page.rel="tag": Indicates that the destination of that hyperlink is an author-designated “tag” (or keyword/subject) for the current page.rel="payment": Indicates that the destination of that hyperlink provides a way to show or give support for the current page.rel="help": States that the resource linked to is a help file or FAQ for the current document.

ARIA roles

The default role of a link is link, so you do not need to do:

<a role="link" href="/">Link</a>You’d only need that if you were faking a link, which would be a weird/rare thing to ever need to do, and you’d have to use some JavaScript in addition to this to make it actually follow the link.

<span class="link" tabindex="0" role="link" data-href="/">

Fake accessible link created using a span

</span>Just looking above you can see how much extra work faking a link is, and that is before you consider that is breaks right-clicking, doesn’t allow opening in a new tab, doesn’t work with Windows High Contrast Mode and other reader modes and assistive technology. Pretty bad!

A useful ARIA role to indicate the current page, like:

<a href="/" aria-current="page">Home</a>

<a href="/contact">Contact</a>

<a href="/about">About/a></a>Should you use the title attribute?

Probably not. Save this for giving an iframe a short, descriptive title.

<a title="I don't need to be here" href="/">

List of Concerts

</a>title provides a hover-triggered UI popup showing the text you wrote. You can’t style it, and it’s not really that accessible.

Hover-triggered is the key phrase here. It’s unusable on any touch-only device. If a link needs more contextual information, provide that in actual content around the link, or use descriptive text the link itself (as opposed to something like “Click Here”).

Icon-only links

If a link only has an icon inside it, like:

<a href="/">😃</a>

<a href="/">

<svg> ... </svg>

</a>That isn’t enough contextual information about the link, particularly for accessibility reasons, but potentially for anybody. Links with text are almost always more clear. If you absolutely can’t use text, you can use a pattern like:

<a href="/">

<!-- Hide the icon from assistive technology -->

<svg aria-hidden="true" focusable="false"> ... </svg>

<!-- Acts as a label that is hidden from view -->

<span class="visually-hidden">Useful link text</span>

</a>visually-hidden is a class used to visually hide the label text with CSS:

.visually-hidden {

border: 0;

clip: rect(0 0 0 0);

height: 1px;

margin: -1px;

overflow: hidden;

padding: 0;

position: absolute;

white-space: nowrap;

width: 1px;

}Unlike aria-label, visually hidden text can be translated and will hold up better in specialized browsing modes.

Links around images

Images can be links if you wrap them in a link. There is no need to use the alt text to say the image is a link, as assistive technology will do that already.

<a href="/buy/puppies/now">

<img src="puppy.jpg" alt="A happy puppy.">

</a>Links around bigger chunks of content

You can link a whole area of content, like:

<a href="/article/">

<div class="card">

<h2>Card</h2>

<img src="..." alt="...">

<p>Content</p>

</div>

</a>But it’s slightly weird, so consider the UX of it if you ever do it. For example, it can be harder to select the text, and the entire element needs styling to create clear focus and hover states.

Take this example, where the entire element is wrapped in a link, but there are no hover and focus states applied to it.

If you need a link within that card element, well, you can’t nest links. You could get a little tricky if you needed ot, like using a pseudo-element on the link which is absolutely positioned to cover the whole area.

Additionally, this approach can make really long and potentially confusing announcements for screen readers. Even though links around chunks of content is technically possible, it’s best to avoid doing this if you can.

Styling and CSS considerations

Here’s the default look of a link:

It’s likely you’ll be changing the style of your links, and also likely you’ll use CSS to do it. I could make all my links red in CSS by doing:

a {

color: red;

}Sometimes selecting and styling all links on a page is a bit heavy-handed, as links in navigation might be treated entirely differently than links within text. You can always scope selectors to target links within particular areas like:

/* Navigation links */

nav a { }

/* Links in an article */

article a { }

/* Links contained in an element with a "text" class */

.text a { }Or select the link directly to style.

.link {

/* For styling <a class="link" href="/"> */

}

a[aria-current="page"] {

/* You'll need to apply this attribute yourself, but it's a great pattern to use for active navigation. */

}Link states

Links are focusable elements. In other words, they can be selected using the Tab key on a keyboard. Links are perhaps the most common element where you’ll very consciously design the different states, including a :focus state.

:hover: For styling when a mouse pointer is over the link.:visited: For styling when the link has been followed, as best as the browser can remember. It has limited styling ability due to security.:link: For styling when a link has not been visited.:active: For styling when the link is pressed (e.g. the mouse button is down or the element is being tapped on a touch screen).:focus: Very important! Links should always have a focus style. If you choose to remove the default blue outline that most browsers apply, also use this selector to re-apply a visually obvious focus style.

These are chainable like any pseudo-class, so you could do something like this if it is useful for your design/UX.

/* Style focus and hover states in a single ruleset */

a:focus:hover { }You can style a link to look button-like

Perhaps some of the confusion between links and buttons is stuff like this:

That certainly looks like a button! Everyone would call that a button. Even a design system would likely call that a button and perhaps have a class like .button { }. But! A thing you can click that says “Learn More” is very much a link, not a button. That’s completely fine, it’s just yet another reminder to use the semantically and functionally correct element.

Color contrast

Since we often style links with a distinct color, it’s important to use a color with sufficient color contrast for accessibility. There is a wide variety of visual impairments (see the tool WhoCanUse for simulating color combinations with different impairments) and high contrast helps nearly all of them.

Perhaps you set a blue color for links:

While that might look OK to you, it’s better to use tools for testing to ensure the color has a strong enough ratio according to researched guidelines. Here, I’ll look at Chrome DevTools and it will tell me this color is not compliant in that it doesn’t have enough contrast with the background color behind it.

Color contrast is a big consideration with links, not just because they are often colored in a unique color that needs to be checked, but because they have all those different states (hover, focus, active, visited) which also might have different colors. Compound that with the fact that text can be selected and you’ve got a lot of places to consider contrast. Here’s an article about all that.

Styling “types” of links

We can get clever in CSS with attribute selectors and figure out what kind of resource a link is pointing to, assuming the href value has useful stuff in it.

/* Style all links that include .pdf at the end */

a[href$=".pdf"]::after {

content: " (PDF)";

}

/* Style links that point to Google */

a[href*="google.com"] {

color: purple;

}Styling links for print

CSS has an “at-rule” for declaring styles that only take effect on printed media (e.g. printing out a web page). You can include them in any CSS like this:

@media print {

/* For links in content, visually display the link */

article a::after {

content: " (" attr(href) ")";

}

}Resetting styles

If you needed to take all the styling off a link (or really any other element for that matter), CSS provides a way to remove all the styles using the all property.

.special-area a {

all: unset;

all: revert;

/* Start from scratch */

color: purple;

}You can also remove individual styles with keywords. (Again, this isn’t really unique to links, but is generically useful):

a {

/* Grab color from nearest parent that sets it */

color: inherit;

/* Wipe out style (turn black) */

color: initial;

/* Change back to User Agent style (blue) */

color: revert;

}JavaScript considerations

Say you wanted to stop the clicking of a link from doing what it normally does: go to that link or jump around the page. In JavaScript, you can usepreventDefault to prevent jumping around.

const jumpLinks = document.querySelectorAll("a[href^='#']");

jumpLinks.forEach(link => {

link.addEventListener('click', event => {

event.preventDefault();

// Do something else instead, like handle the navigation behavior yourself

});

});This kind of thing is at the core of how “Single Page Apps” (SPAs) work. They intercept the clicks so browsers don’t take over and handle the navigation.

SPAs see where you are trying to go (within your own site), load the data they need, replace what they need to on the page, and update the URL. It’s an awful lot of work to replicate what the browser does for free, but you get the ability to do things like animate between pages.

Another JavaScript concern with links is that, when a link to another page is clicked, the page is left and another page loads. That can be problematic for something like a page that contains a form the user is filling out but hasn’t completed. If they click the link and leave the page, they lose their work! Your only opportunity to prevent the user from leaving is by using the beforeunload event.

window.addEventListener("beforeunload", function(event) {

// Remind user to save their work or whatever.

});A link that has had its default behavior removed won’t announce the new destination. This means a person using assistive technology may not know where they wound up. You’ll have to do things like update the page’s title and move focus back up to the top of the document.

JavaScript frameworks

In a JavaScript framework, like React, you might sometimes see links created from something like a component rather than a native element. The custom component probably creates a native element, but with extra functionality, like enabling the JavaScript router to work, and adding attributes like aria-current="page" as needed, which is a good thing!

Ultimately, a link is a link. A JavaScript framework might offer or encourage some level of abstraction, but you’re always free to use regular links.

Accessibility considerations

We covered some accessibility in the sections above (it’s all related!), but here are some more things to think about.

- You don’t need text like “Link” or “Go to” in the link text itself. Make the text meaningful (“documentation” instead of “click here”).

- Links already have an ARIA role by default (

role="link") so there’s no need to explicitly set it. - Try not to use the URL itself as the text (

google.com) - Links are generally blue and generally underlined and that’s generally good.

- All images in content should have

alttext anyway, but doubly so when the image is wrapped in a link with otherwise no text.

Unique accessible names

Some assistive technology can create lists of interactive elements on the page. Imagine a group of four article cards that all have a “Read More”, the list of interactive elements will be like:

- Read More

- Read More

- Read More

- Read More

Not very useful. You could make use of that .visually-hidden class we covered to make the links more like:

<a href="/article">

Read More

<span class="visually-hidden">

of the article "Dancing with Rabbits".

<span>

</a>Now each link is unique and clear. If the design can support it, do it without the visually hidden class to remove the ambiguity for everyone.

Buttons

Buttons are for triggering actions. When do you use the element? A good rule is to use a button when there is “no meaningful href.” Here’s another way to think of that: if clicking it doesn’t do anything without JavaScript, it should be a .

A that is within a , by default, will submit that form. But aside from that, button elements don’t have any default behavior, and you’ll be wiring up that interactivity with JavaScript.

Table of Contents

HTML implementation

<button>Buy Now</button>Buttons inside of a do something by default: they submit the form! They can also reset it, like their input counterparts. The type attributes matter:

<form action="/" method="POST">

<input type="text" name="name" id="name">

<button>Submit</button>

<!-- If you want to be more explicit... -->

<button type="submit">Submit</button>

<!-- ...or clear the form inputs back to their initial values -->

<button type="reset">Reset</button>

<!-- This prevents a `submit` action from firing which may be useful sometimes inside a form -->

<button type="button">Non-submitting button</button>

</form>Speaking of forms, buttons have some neat tricks up their sleeve where they can override attributes of the itself.

<form action="/" method="get">

<!-- override the action -->

<button formaction="/elsewhere/" type="submit">Submit to elsewhere</button>

<!-- override encytype -->

<button formenctype="multipart/form-data" type="submit"></button>

<!-- override method -->

<button formmethod="post" type="submit"></button>

<!-- do not validate fields -->

<button formnovalidate type="submit"></button>

<!-- override target e.g. open in new tab -->

<button formtarget="_blank" type="submit"></button>

</form>Autofocus

Since buttons are focusable elements, we can automatically focus on them when the page loads using the autofocus attribute:

<div class="modal">

<h2>Save document?</h2>

<button>Cancel</button>

<button autofocus>OK</button>

</div>Perhaps you’d do that inside of a modal dialog where one of the actions is a default action and it helps the UX (e.g. you can press Enter to dismiss the modal). Autofocusing after a user action is perhaps the only good practice here, moving a user’s focus without their permission, as the autofocus attribute is capable of, can be a problem for screen reader and screen magnifier users.

Note thatautofocus may not work if the element is within an for security reasons.

Disabling buttons

To prevent a button from being interactive, there is a disabled attribute you can use:

<button disabled>Pay Now</button>

<p class="error-message">Correct the form above to submit payment.</p>Note that we’ve included descriptive text alongside the disabled button. It can be very frustrating to find a disabled button and not know why it’s disabled. A better way to do this could be to let someone submit the form, and then explain why it didn’t work in the validation feedback messaging.

Regardless, you could style a disabled button this way:

/* Might be good styles for ANY disabled element! */

button[disabled] {

opacity: 0.5;

pointer-events: none;

} We’ll cover other states and styling later in this guide.

Buttons can contain child elements

A submit button and a submit input () are identical in functionality, but different in the sense that an input is unable to contain child elements while a button can.

<button>

<svg aria-hidden="true" focusable="false">

<path d="..." />

</svg>

<span class="callout">Big</span>

Sale!

</button>

<button type="button">

<span role="img" aria-label="Fox">

🦊

</span>

Button

</button>Note the focusable="false" attribute on the SVG element above. In that case, since the icon is decorative, this will help assistive technology only announce the button’s label.

Styling and CSS considerations

Buttons are generally styled to look very button-like. They should look pressable. If you’re looking for inspiration on fancy button styles, you’d do well looking at the CodePen Topic on Buttons.

Cross-browser/platform button styles

How buttons look by default varies by browser and platform.

border: 0; to those same buttons as above, and we have different styles entirely.While there is some UX truth to leaving the defaults of form elements alone so that they match that browser/platform’s style and you get some affordance for free, designers typically don’t like default styles, particularly ones that differ across browsers.

Resetting the default button style

Removing all the styles from a button is easier than you think. You’d think, as a form control, appearance: none; would help, but don’t count on that. Actually all: revert; is a better bet to wipe the slate clean.

You can see how a variety of properties are involved

And that’s not all of them. Here’s a consolidated chunk of what Normalize does to buttons.

button {

font-family: inherit; /* For all browsers */

font-size: 100%; /* For all browsers */

line-height: 1.15; /* For all browsers */

margin: 0; /* Firefox and Safari have margin */

overflow: visible; /* Edge hides overflow */

text-transform: none; /* Firefox inherits text-transform */

-webkit-appearance: button; /* Safari otherwise prevents some styles */

}

button::-moz-focus-inner {

border-style: none;

padding: 0;

}

button:-moz-focusring {

outline: 1px dotted ButtonText;

}A consistent .button class

In addition to using reset or baseline CSS, you may want to have a class for buttons that gives you a strong foundation for styling and works across both links and buttons.

.button {

border: 0;

border-radius: 0.25rem;

background: #1E88E5;

color: white;

font-family: -system-ui, sans-serif;

font-size: 1rem;

line-height: 1.2;

white-space: nowrap;

text-decoration: none;

padding: 0.25rem 0.5rem;

margin: 0.25rem;

cursor: pointer;

}Check out this Pen to see why all these properties are needed to make sure it works correctly across elements.

Button states

Just as with links, you’ll want to style the states of buttons.

button:hover { }

button:focus { }

button:active { }

button:visited { } /* Maybe less so */You may also want to use ARIA attributes for styling, which is a neat way to encourage using them correctly:

button[aria-pressed="true"] { }

button[aria-pressed="false"] { }Link-styled buttons

There are always exceptions. For example, a website in which you need a button-triggered action within a sentence:

<p>You may open your <button>user settings</button> to change this.</p>We’ve used a button instead of an anchor tag in the above code, as this hypothetical website opens user settings in a modal dialog rather than linking to another page. In this situation, you may want to style the button as if it looks like a link.

This is probably rare enough that you would probably make a class (e.g. .link-looking-button) that incorporates the reset styles from above and otherwise matches what you do for anchor links.

Breakout buttons

Remember earlier when we talked about the possibility of wrapping entire elements in links? If you have a button within another element, but you want that entire outer element to be clickable/tappable as if it’s the button, that’s a “breakout” button. You can use an absolutely-positioned pseudo-element on the button to expand the clickable area to the whole region. Fancy!

JavaScript considerations

Even without JavaScript, button elements can be triggered by the Space and Enter keys on a keyboard. That’s part of what makes them such appealing and useful elements: they are discoverable, focusable, and interactive with assistive technology in a predictable way.

Perhaps any in that situation should be inserted into the DOM by JavaScript. A tall order! Food for thought. ?

“Once” handlers

Say a button does something pretty darn important, like submitting a payment. It would be pretty scary if it was programmed such that clicking the button multiple times submitted multiple payment requests. It is situations like this where you would attach a click handler to a button that only runs once. To make that clear to the user, we’ll disable the button on click as well.

document.querySelector("button").addEventListener('click', function(event) {

event.currentTarget.setAttribute("disabled", true);

}, {

once: true

});Then you would intentionally un-disable the button and reattach the handler when necessary.

Inline handlers

JavaScript can be executed by activating a button through code on the button itself:

<button onclick="console.log('clicked');">

Log it.

</button>

<button onmousedown="">

</button>

<button onmouseup="">

</button>That practice went from being standard practice to being a faux pas (not abstracting JavaScript functionality away from HTML) to, eh, you need it when you need it. One advantage is that if you’re injecting this HTML into the DOM, you don’t need to bind/re-bind JavaScript event handlers to it because it already has one.

JavaScript frameworks

It’s common in any JavaScript framework to make a component for handling buttons, as buttons typically have lots of variations. Those variations can be turned into an API of sorts. For example, in React:

const Button = ({ className, children }) => {

const [activated, setActivated] = React.useState(false);

return (

<button

className={`button ${className}`}

aria-pressed={activated ? "true" : "false")

onClick={() => setActivated(!activated)}

>

{children}

</button>

);

};In that example, the component ensures the button will have a button class and handles a toggle-like active class.

Accessibility considerations

The biggest accessibility consideration with buttons is actually using buttons. Don’t try to replicate a button with a

Focus styles

Like all focusable elements, browsers apply a default focus style, which is usually a blue outline.

While it’s arguable that you should leave that alone as it’s a very clear and obvious style for people that benefit from focus styles, it’s also not out of the question to change it.

What you should not do is button:focus { outline: 0; } to remove it. If you ever remove a focus style like that, put it back at the same time.

button:focus {

outline: 0; /* Removes the default blue ring */

/* Now, let's create our own focus style */

border-radius: 3px;

box-shadow: 0 0 0 2px red;

}

The fact that a button may become focused when clicked and apply that style at the same time is offputting to some. There is a trick (that has limited, but increasing, browser support) on removing focus styles from clicks and not keyboard events:

:focus:not(:focus-visible) {

outline: 0;

}ARIA

Buttons already have the role they need (role="button"). But there are some other ARIA attributes that are related to buttons:

aria-pressed: Turns a button into a toggle, betweenaria-pressed="true"andaria-pressed="false". More on button toggles, which can also be done withrole="switch"andaria-checked="true".aria-expanded: If the button controls the open/closed state of another element (like a dropdown menu), you apply this attribute to indicate that likearia-expanded="true".aria-label: Overrides the text within the button. This is useful for labeling buttons that otherwise don’t have text, but you’re still probably better off using avisually-hiddenclass so it can be translated.aria-labelledby: Points to an element that will act as the label for the button.

For that last one:

<button aria-labelledby="buttonText">

Time is running out!

<span id="buttonText">Add to Cart</span>

</button>Deque has a deeper dive blog post into button accessibility that includes much about ARIA.

Dialogs

If a button opens a dialog, your job is to move the focus inside and trap it there. When closing the dialog, you need to return focus back to that button so the user is back exactly where they started. This makes the experience of using a modal the same for someone who relies on assistive technology as for someone who doesn’t.

Focus management isn’t just for dialogs, either. If clicking a button runs a calculation and changes a value on the page, there is no context change there, meaning focus should remain on the button. If the button does something like “move to next page,” the focus should be moved to the start of that next page.

Size

Don’t make buttons too small. That goes for links and any sort of interactive control. People with any sort of reduced dexterity will benefit.

The classic Apple guideline for the minimum size for a touch target (button) is 44x44pt.

Here’s some guidelines from other companies. Fitt’s Law tells us smaller targets have greater error rates. Google even takes button sizes into consideration when evaluating the SEO of a site.

In addition to ample size, don’t place buttons too close each other, whether they’re stacked vertically or together on the same line. Give them some margin because people experiencing motor control issues run the risk of clicking the wrong one.

Activating buttons

Buttons work by being clicked/touched, pressing the Enter key, or pressing the Space key (when focused). Even if you add role="button" to a link or div, you won’t get the spacebar functionality, so at the risk of beating a dead horse, use in those cases.

The post A Complete Guide to Links and Buttons appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

Designing Ethically, Optimizing Videos, And Shining The Spotlight On Our SmashingConf Speakers

Designing Ethically, Optimizing Videos, And Shining The Spotlight On Our SmashingConf Speakers

Iris Lješnjanin2020-02-14T14:00:00+00:002020-02-14T17:06:44+00:00

An important part of our job is staying up to date, and we know how difficult it can be. Technologies don’t really change that fast — coding languages take a long time to be specified and implemented. But the ideas surrounding these technologies and the things we can do with them are constantly evolving, and hundreds of blog posts and articles are published every day. There’s no way you can read all of those but you’ll still have to keep up to date.

Fear not, we’ve got your backs! Our bi-weekly Smashing Podcast has you covered with a variety of topics across multiple levels of expertise.

A shout-out and big thank you to both Drew McLellan and Bethany Andrew for making the episodes so brilliantly witty and informative!

- Previous episodes (including transcripts)

- Follow @SmashingPod on Twitter

A Lovely New Addition To The Smashing Books

We’re so proud to be introducing a new book to the Smashing bookshelf — a cover so eloquently designed and a book that covers topics that are very close to our hearts: ethics and privacy.

The “The Ethical Design Handbook” is our new guide on ethical design for digital products that respect customer choices and are built and designed with ethics in mind. It’s full of practical guidelines on how to make ethical decisions to influence positive change and help businesses grow in a sustainable way.

Of course, you can jump right over to the table of contents and see for yourself, but be sure to pre-order the book while you can! There’s still a discount available before the official release — we’ll start shipping printed hardcover copies in the first two weeks of March! Stay tuned!

Learning And Networking, The Smashing Way

Our SmashingConfs are known to be friendly, inclusive events where front-end developers and designers come together to attend live sessions and hands-on workshops. From live designing to live debugging, we want you to ask speakers anything — from naming conventions to debugging strategies. For each talk, we’ll have enough time to go into detail, and show real examples from real work on the big screen.

We like to bring you closer to folks working in the web industry, and so every once in a while we interview the speakers who share the stage! For SmashingConf Austin, the spotlight shined on:

- Miriam Suzanne, who’ll be talking about the wonderful new world of CSS, new techniques and possibilities.

- Zach Leatherman, who’ll let us in on everything we need to know about type,font performance tooling and general workflow when it comes to web fonts.

- Rémi Parmentier, who’ll bring us closer to the good ol’ HTML Email, common techniques, state of things and what you can achieve with HTML Email today (if you are willing enough to explore its unconventional world).

Shining The Spotlight On Optimizing Video Files

Mark your calendars! In less than two weeks (Feb. 25, we’ll be hosting a Smashing TV webinar with Doug Sillars who’ll be sharing several possible scenarios to optimize video files for fast and efficient playback on the web. Join us at 17:00 London time — we’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences you’ve had in your career!

We often get asked who the creative talent behind the illustrations is: It’s the one-and-only Ricardo Gimenes, someone we’re ever so proud to have in our team!

Trending Topics On SmashingMag

We publish a new article every day on various topics that are current in the web industry. Here are some that our readers seemed to enjoy the most and have recommended further:

- “How To Create Maps With React And Leaflet”

by Shajia Abidi

Leaflet is a very powerful tool, and we can create a lot of different kinds of maps. This tutorial will help you understand how to create an advanced map along with the help of React and Vanilla JS. - “Understanding CSS Grid: Grid Template Areas”

by Rachel Andrew

In a new series, Rachel Andrew breaks down the CSS Grid Layout specification. This time, she takes us throughgrid-template-areasand how it can be used to place items. - “How To Create A Headless WordPress Site On The JAMstack”

by Sarah Drasner & Geoff Graham

In this post, Sarah and Geoff set up a demo site and tutorial for headless WordPress — including a starter template! They explain how to set up a Vue application with Nuxt, pulling in the posts from our application via the WordPress API. - “Magic Flip Cards: Solving A Common Sizing Problem”

by Dan Halliday

In this article, Dan reviews the standard approach to creating animated flip cards and introduces an improved method which solves its sizing problem.

Best Picks From Our Newsletter

With the start of a brand-new decade, we decided to start off with topics dedicated to web performance. There are so many talented folks out there working on brilliant projects, and we’d love to spread the word and give them the credit they deserve!

Note: A huge thank you to Cosima Mielke for writing and preparing these posts!

Tiny Helpers For Web Developers

Minifying an SVG, extracting CSS from HTML, or checking your color palette for accessibility — we all know those moments when we need a little tool to help us complete a task quickly and efficiently. If you ever find yourself in such a situation again, Tiny Helpers might have just the tool you’re looking for.

Maintained by Stefan Judis, Tiny Helpers is a collection of free, single-purpose online tools for web developers. The tools cover everything from APIs, accessibility, and color, to fonts, performance, regular expressions, SVG, and unicode. And if you know of a useful tool that isn’t featured yet, you can submit a pull request with your suggestion. One for the bookmarks.

Real-World Color Palette Inspiration

There are a lot of fantastic sites out there that help you find inspiring color palettes. However, once you have found a palette you like, the biggest question is still left unanswered: how should you apply the colors to your design? Happy Hues is here to help.

Designed by Mackenzie Child, Happy Hues gives you color palette inspiration while acting as a real-world example for how the colors could be used in your design. Just change the palette, and the Happy Hues site changes its colors to show you what your favorite palette looks like in an actual design. Clever!

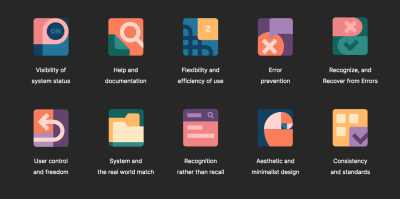

Free Usability Heuristics Posters

Back in 1994, Jakob Nielsen wrote an article for Nielsen Norman Group, outlining general principles for interface design: the 10 usability heuristics. Today, decades later, these heuristics still serve as a checklist for interface designers. A fact that inspired the folks at Agente Studio to create a set of posters dedicated to them.

Each of the ten beautifully-designed posters illustrates and explains one of Nielsen’s heuristics. The posters are CC-licensed and can be downloaded and printed for free after you shared the page on social media. JPEG and EPS formats are available.

A Guide To Fighting Online Tracking

It’s no secret that we’re being tracked online. And while we can’t stop all of it, there are things we can do to fight back.

In his New York Times article, Tim Herrera dives deeper into the data companies collect about us and how they share it with third parties, into “secret scores” and shocking third-party reports that list our delivery service orders and private Airbnb messages from years ago. Besides being a good reminder to be more wary of handing out our data, the article features links to tools and practical tips for preventing advertiser tracking. A must-read.

The Illustrated Children’s Guide To Kubernetes

Have you ever tried to explain software engineering to a child or to a friend, colleague, or relative who isn’t that tech-savvy? Well, finding easy words to explain a complex concept can be a challenge. A challenge that “The Illustrated Children’s Guide to Kubernetes” masters beautifully.

Designed as a storybook and available to be read online or as a PDF, the free guide tells the story of a PHP app named Phippy who wished she had her own environment, just her and a webserver she could call home. On her journey, she meets Captain Kube who gives her a new home on his ship Kubernetes. A beautiful metaphor to explain the core concept of Kubernetes.

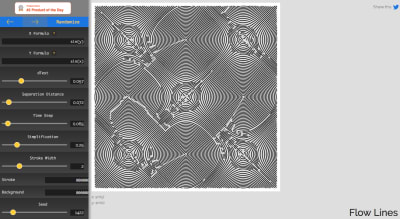

Generator Of Geometric Shapes

To stand out from the crowd of a myriad of websites out there, we can define one unique thing, the signature, that brings a bit of personality into our digital products. Perhaps it’s a little glitch effect, or a pencil scribble, a game or unusual shapes. Or, it could be a set of seemingly random geometric flow lines.

Flow Lines Generator produces random geometric lines, and we can adjust the formulas and distances between the shapes drawn, and then export the outcome as SVG. Perhaps every single page on your site could have a variation of these lines in some way? It might be enough to stand out from the crowd, mostly because nobody else has that exact visual treatment. It might be worth looking at!

Git From Beginner To Advanced

Most of us will be dealing with Git regularly, sometimes running Git commands from terminal, and sometimes using a visual tool to pull, push, commit and merge. If you feel like you’d like to supercharge your skills and gain a few Git superpowers, where do you start?

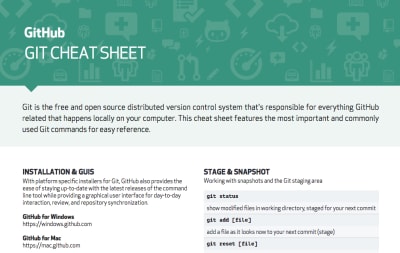

Mike Riethmueller has published a quick guide to Git, from beginner to advanced, explaining how Git works, how to configure it, aliases, important commands, staging/unstaging files, managing merge conflicts, stashing and a few advanced tips. Need more advanced stuff? Harry Roberts has published “Little Things I Like To Do With Git”, Atlassian has Advanced Git Tutorials, Bruno Passos lists useful git commands, and GitHub provides a Git Cheat Sheet PDF.

The Museum Of Obsolete Media

Do you remember the days when you listened to a music cassette on your Walkman, watched your favorite movie on video tape instead of streaming it, or stored your data on a floppy disk? The media we considered state-of-the-art back then, is obsolete today. And, well, a lot of other formats shared the same fate in the past.

In his Museum of Obsolete Media, Jason Curtis collects examples of media that went out of use, not just the ones you might remember, but also real curiosities and treasures dating back as far as to the middle of the 19th century. Things like the “carte de visite”, “Gould Moulded Records”, or “Magnabelt” for example. A fascinating trip back in time.

Each and every issue of the Smashing Newsletter is written and edited with love and care. No third-party mailings or hidden advertising — you’ve got our word.

Smashing Newsletter

Upgrade your inbox and get our editors’ picks 2× a month — delivered right into your inbox. Earlier issues.

Useful tips for web designers. Sent 2× a month.

You can unsubscribe any time — obviously.

(cm, vf, ra, il)

(cm, vf, ra, il)

Pros and Cons of Using AI to Improve Road Safety

Did you know that roads are deadlier than wars?

Throughout the entire 20th century, a period when the First and Second World Wars took place, the generally accepted death toll stemming from political conflicts was 108 million. However, around 1.35 million individuals lose their lives as a result of a road traffic accident every year, according to the World Health Organization.

Although one could argue that the fatalities on the roads are accidental and those in the battlefields are intentional, the statistics do not lie – we are likelier to get hit by a vehicle driven by a civilian than a bullet coming from a gun barrel of a state enemy.

This notion is true even in the United States, which is a high-profile target of terrorists. From 1995 to 2016, terrorism claimed the lives of just 3,277 persons in the US. But our friends at PolicyAdvice discovered that car collisions cut about 40,000 Americans off in their prime in 2018 alone.

Yet, some of us are more afraid of sitting next to a racially profiled “terrorist” than crossing an intersection.

Fortunately, road safety improvement has been getting into the consciousness of the general public of late. One of the things to thank for is the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI).

After decades of receiving generous R&D funding, AI has matured and become commercially viable enough to inspire wide-scale adoption in many industries, including transportation.

Can this technology feasibly make our roads way safer? If so, how? The jury is still out on whether AI is truly the lifesaver it is billed as. But the world remains somewhat divided over its utility in road safety since it has its own share of merits and flaws.

The Pros of AI in Road Safety

Eliminating Driver-Inflicted Car Crashes

Driver error is the number one cause of road traffic crashes. It should not come as a surprise, for humans are too stubborn not to drive while distracted, intoxicated, high, or drowsy.

The obvious solution to such risky driver behavior is to pass the steering wheel to something incapable of getting distracted, intoxicated, high, and drowsy while driving the way humans do. Hence the need for vehicle autonomy.

Some technologists think that we are still decades away from seeing Level-5 autonomous vehicles (AVs) on the roads, but the tech has already been aiding motorists via advanced driver assistance system.

The ultimate goal of AV developers, however, is to put AI in the driver’s seat from the get-go. On paper, it makes total sense because computers can be better drivers than experienced human drivers themselves.

Self-driving vehicles are equipped with cutting-edge cameras, sensors, and radars to perceive the surroundings and other road users in order to predict the unpredictable in ways we can never do with our limited and inferior senses.

These futuristic cars and trucks also react to hazards more quickly. In addition, vehicle-to-vehicle communication could let them exchange information instantaneously and warn one another about nearby dangers.

Determining Dangerous Routes

AI-powered vehicles may run on gas and/or electricity, but they are fueled by data. Intelligent cars and trucks constantly gather information that can produce actionable insights with proper analytics.

Transport interests can use such findings to detect which stretches of roads are inherently dangerous due to one reason or another in order to plan safer routes for drivers.

Streamlining Traffic Patterns

AI and big data analytics can help the authorities control the flow of vehicular traffic in different areas. Traffic managers will be able to make informed decisions to prevent congestion in urban locations or at least minimize gridlocks during rush hour. That said, they would serve public transport commuters more efficiently.

Furthermore, AI plays crucial roles in predicting the paths of vulnerable road users, such as pedestrians and cyclists. AI-driven traffic management can translate to diverse mobility options, reduced number of accidents and casualties, and minimal greenhouse gas emissions.

Reacting to Emergencies

Some vehicle models use AI to better address emergencies. The tech gave birth to auto features that can detect health conditions like a heart attack, request for medical services, and give relevant parties key details like vehicle location. Such capabilities are particularly useful for truck drivers who work at night.

Identifying Driver Weaknesses

Using AI, along with other innovations like facial recognition tech, fleet managers can monitor driver performance in real time. This luxury not only enables decision-makers to dispatch relief drivers accordingly but also uncover bad driver habits. The availability of such data allows transport companies to provide proper training to certain drivers.

The Cons of AI in Road Safety

Raising Ethical Issues

AVs have the potential to save lives. But it would be naïve to think that they will never scratch or kill someone at some point. In fact, they already did.

So when it is impossible to save all potential casualties in a crash, who should decide who gets to live or who gets hit?

Are humans always more precious than animals? Is the life of a child more important than those of commuters riding a bus? Should productive adults be prioritized over old people? Should an AV swerve into the path of pedestrians to avoid a speeding motorcycle and protect its own passengers? If someone gets injured or dies, who should be held accountable for the behavior of a self-driving vehicle?

These ethical questions must be discussed by automotive industry leaders and maybe policymakers too. However, the software of AVs is designed to make judgment calls in life-threatening situations, and it is not going to please everybody.

Getting Exposed to Cyberattacks

Connected vehicles can be hacked, so cybersecurity is a serious concern. Anyone capable of hijacking the system of any specific AI-powered vehicle might choose to do so, irrespective of motivation. Such an incident could start a media frenzy and cause intense social panic.

Requiring Significant Funds to Adopt

The adoption of an AI-driven system for traffic management at any level could require enormous funds. For this reason, countries and communities with fewer resources might not be able to embrace such solutions as quickly as wealthier ones could. Without the necessary infrastructure in place, the tech can’t do much for road users.

Final Word

AI definitely has a place in future road safety. Many of its use cases in transportation are already being tested, if not implemented. We may not be able to anticipate the full extent of its impact on society in the long run, but the best we could do is to develop it with foresight in hopes of successfully solving our pressing problems with road safety without creating new ones we could not effectively remedy.

Why JavaScript is Eating HTML

Web development is always changing. One trend in particular has become very popular lately, and it fundamentally goes against the conventional wisdom about how a web page should be made. It is exciting for some but frustrating for others, and the reasons for both are difficult to explain.

A web page is traditionally made up of three separate parts with separate responsibilities: HTML code defines the structure and meaning of the content on a page, CSS code defines its appearance, and JavaScript code defines its behavior. On teams with dedicated designers, HTML/CSS developers and JavaScript developers, this separation of concerns aligns nicely with job roles: Designers determine the visuals and user interactions on a page, HTML and CSS developers reproduce those visuals in a web browser, and JavaScript developers add the user interaction to tie it all together and “make it work.” People can work on one piece without getting involved with all three.

In recent years, JavaScript developers have realized that by defining a page’s structure in JavaScript instead of in HTML (using frameworks such as React), they can simplify the development and maintenance of user interaction code that is otherwise much more complex to build. Of course, when you tell someone that the HTML they wrote needs to be chopped up and mixed in with JavaScript they don’t know anything about, they can (understandably) become frustrated and start asking what the heck we’re getting out of this.

As a JavaScript developer on a cross-functional team, I get this question occasionally and I often have trouble answering it. All of the materials I’ve found on this topic are written for an audience that is already familiar with JavaScript — which is not terribly useful to those who focus on HTML and CSS. But this HTML-in-JS pattern (or something else that provides the same benefits) will likely be around for a while, so I think it’s an important thing that everyone involved in web development should understand.

This article will include code examples for those interested, but my goal is to explain this concept in a way that can be understood without them.

Background: HTML, CSS, and JavaScript

To broaden the audience of this article as much as possible, I want to give a quick background on the types of code involved in creating a web page and their traditional roles. If you have experience with these, you can skip ahead.

HTML is for structure and semantic meaning

HTML (HyperText Markup Language) code defines the structure and meaning of the content on a page. For example, this article’s HTML contains the text you’re reading right now, the fact that it is in a paragraph, and the fact that it comes after a heading and before a CodePen.

Let’s say we want to build a simple shopping list app. We might start with some HTML like this:

We can save this code in a file, open it in a web browser, and the browser will display the rendered result. As you can see, the HTML code in this example represents a section of a page that contains a heading reading “Shopping List (2 items),” a text input box, a button reading “Add Item,” and a list with two items reading “Eggs” and “Butter.” In a traditional website, a user would navigate to an address in their web browser, then the browser would request this HTML from a server, load it and display it. If there are already items in the list, the server could deliver HTML with the items already in place, like they are in this example.

Try to type something in the input box and click the “Add Item” button. You’ll notice nothing happens. The button isn’t connected to any code that can change the HTML, and the HTML can’t change itself. We’ll get to that in a moment.

CSS is for appearance

CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) code defines the appearance of a page. For example, this article’s CSS contains the font, spacing, and color of the text you’re reading.

You may have noticed that our shopping list example looks very plain. There is no way for HTML to specify things like spacing, font sizes, and colors. This is where CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) comes in. On the same page as the HTML above, we could add CSS code to style things up a bit:

As you can see, this CSS changed the font sizes and weights and gave the section a nice background color (designers, please don’t @ me; I know this is still ugly). A developer can write style rules like these and they will be applied consistently to any HTML structure: if we add more

elements to this page, they will have the same font changes applied.

The button still doesn’t do anything, though: that’s where JavaScript comes in.

JavaScript is for behavior

JavaScript code defines the behavior of interactive or dynamic elements on a page. For example, the embedded CodePen examples in this article are powered by JavaScript.

Without JavaScript, to make the Add Item button in our example work would require us to use special HTML to make it submit data back to the server (, if you’re curious). Then the browser would discard the entire page and reload an updated version of the entire HTML file. If this shopping list was part of a larger page, anything else the user was doing would be lost. Scrolled down? You’re back at the top. Watching a video? It starts over. This is how all web applications worked for a long time: any time a user interacted with a webpage, it was as if they closed their web browser and opened it again. That’s not a big deal for this simple example, but for a large complex page which could take a while to load, it’s not efficient for either the browser or the server.

If we want anything to change on a webpage without reloading the entire page, we need JavaScript (not to be confused with Java, which is an entirely different language… don’t get me started). Let’s try adding some:

Now when we type some text in the box and click the “Add Item” button, our new item is added to the list and the item count at the top is updated! In a real app, we would also add some code to send the new item to the server in the background so that it will still show up the next time we load the page.

Separating JavaScript from the HTML and CSS makes sense in this simple example. Traditionally, even more complicated interactions would be added this way: HTML is loaded and displayed, and JavaScript runs afterwards to add things to it and change it. As things get more complex, however, we start needing to keep better track of things in our JavaScript.

If we were to keep building this shopping list app, next we’d probably add buttons for editing or removing items from the list. Let’s say we write the JavaScript for a button that removes an item, but we forget to add the code that updates the item total at the top of the page. Suddenly we have a bug: after a user removes an item, the total on the page won’t match the list! Once we notice the bug, we fix it by adding that same totalText.innerHTML line from our “Add Item” code to the “Remove Item” code. Now we have the same code duplicated in more than one place. Later on, let’s say we want to change that code so that instead of “(2 items)” at the top of the page it reads “Items: 2.” We’ll have to make sure we update it in all three places: in the HTML, in the JavaScript for the “Add Item” button, and in the JavaScript for the “Remove Item” button. If we don’t, we’ll have another bug where that text abruptly changes after a user interaction.

In this simple example, we can already see how quickly these things can get messy. There are ways to organize our JavaScript to make this kind of problem easier to deal with, but as things continue to get more complex, we’ll need to keep restructuring and rewriting things to keep up. As long as HTML and JavaScript are kept separate, a lot of effort can be required to make sure everything is kept in sync between them. That’s one of the reasons why new JavaScript frameworks, like React, have gained traction: they are designed to show the relationships between things like HTML and JavaScript. To understand how that works, we first need to understand just a teeny bit of computer science.

Two kinds of programming

The key concept to understand here involves the distinction between two common programming styles. (There are other programming styles, of course, but we’re only dealing with two of them here.) Most programming languages lend themselves to one or the other of these, and some can be used in both ways. It’s important to grasp both in order to understand the main benefit of HTML-in-JS from a JavaScript developer’s perspective.

- Imperative programming: The word “imperative” here implies commanding a computer to do something. A line of imperative code is a lot like an imperative sentence in English: it gives the computer a specific instruction to follow. In imperative programming, we must tell the computer exactly how to do every little thing we need it to do. In web development, this is starting to be considered “the old way” of doing things and it’s what you do with vanilla JavaScript, or libraries like jQuery. The JavaScript in my shopping list example above is imperative code.

- Imperative: “Do X, then do Y, then do Z”.

- Example: When the user selects this element, add the

.selectedclass to it; and when the user de-selects it, remove the.selectedclass from it.

- Declarative programming: This is a more abstract layer above imperative programming. Instead of giving the computer instructions, we instead “declare” what we want the results to be after the computer does something. Our tools (e.g. React) figure out the how for us automatically. These tools are built with imperative code on the inside that we don’t have to pay attention to from the outside.

- Declarative: “The result should be XYZ. Do whatever you need to do to make that happen.”

- Example: This element has the

.selectedclass if the user has selected it.

HTML is a declarative language

Forget about JavaScript for a moment. Here’s an important fact: HTML on its own is a declarative language. In an HTML file, you can declare something like:

<section>

<h1>Hello</h1>

<p>My name is Mike.</p>

</section>When a web browser reads this HTML, it will figure out these imperative steps for you and execute them:

- Create a section element

- Create a heading element of level 1

- Set the inner text of the heading element to “Hello”

- Place the heading element into the section element

- Create a paragraph element

- Set the inner text of the paragraph element to “My name is Mike”

- Place the paragraph element into the section element

- Place the section element into the document

- Display the document on the screen

As a web developer, the details of how a browser does these things is irrelevant; all that matters is that it does them. This is a perfect example of the difference between these two kinds of programming. In short, HTML is a declarative abstraction wrapped around a web browser’s imperative display engine. It takes care of the “how” so you only have to worry about the “what.” You can enjoy life writing declarative HTML because the fine people at Mozilla or Google or Apple wrote the imperative code for you when they built your web browser.

JavaScript is an imperative language

We’ve already looked at a simple example of imperative JavaScript in the shopping list example above, and I mentioned how the complexity of an app’s features has ripple effects on the effort required to implement them and the potential for bugs in that implementation. Now let’s look at a slightly more complex feature and see how it can be simplified by using a declarative approach.

Imagine a webpage that contains the following:

- A list of labelled checkboxes, each row of which changes to a different color when it is selected

- Text at the bottom like “1 of 4 selected” that should update when the checkboxes change

- A “Select All” button which should be disabled if all checkboxes are already selected

- A “Select None” button which should be disabled if no checkboxes are selected

Here’s an implementation of this in plain HTML, CSS and imperative JavaScript:

There isn’t much CSS code here because I’m using the wonderful PatternFly design system, which provides most of the CSS for my example. I imported their CSS file in the CodePen settings.

All the small things

In order to implement this feature with imperative JavaScript, we need to give the browser several granular instructions. This is the English-language equivalent to the code in my example above:

- In our HTML, we declare the initial structure of the page:

- There are four row elements, each containing a checkbox. The third box is checked.

- There is some summary text which reads “1 of 4 selected.”

- There is a “Select All” button which is enabled.

- There is a “Select None” button which is disabled.

- In our JavaScript, we write instructions for what to change when each of these events occurs:

- When a checkbox changes from unchecked to checked:

- Find the row element containing the checkbox and add the

.selectedCSS class to it. - Find all the checkbox elements in the list and count how many are checked and how many are not checked.

- Find the summary text element and update it with the checked number and the total number.

- Find the “Select None” button element and enable it if it was disabled.

- If all checkboxes are now checked, find the “Select All” button element and disable it.

- Find the row element containing the checkbox and add the

- When a checkbox changes from checked to unchecked:

- Find the row element containing the checkbox and remove the

.selectedclass from it. - Find all the checkbox elements in the list and count how many are checked and not checked.

- Find the summary text element and update it with the checked number and the total number.

- Find the “Select All” button element and enable it if it was disabled.

- If all checkboxes are now unchecked, find the “Select None” button element and disable it.

- Find the row element containing the checkbox and remove the

- When the “Select All” button is clicked:

- Find all the checkbox elements in the list and check them all.

- Find all the row elements in the list and add the

.selectedclass to them. - Find the summary text element and update it.

- Find the “Select All” button and disable it.

- Find the “Select None” button and enable it.

- When the “Select None” button is clicked:

- Find all the checkbox elements in the list and uncheck them all.

- Find all the row elements in the list and remove the

.selectedclass from them. - Find the summary text element and update it.

- Find the “Select All” button and enable it.

- Find the “Select None” button and disable it.

- When a checkbox changes from unchecked to checked:

Wow. That’s a lot, right? Well, we better remember to write code for each and every one of those things. If we forget or screw up any of those instructions, we will end up with a bug where the totals don’t match the checkboxes, or a button is enabled that doesn’t do anything when you click it, or a row ends up with the wrong color, or something else we didn’t think of and won’t find out about until a user complains.

The big problem here is that there is no single source of truth for the state of our app, which in this case is “which checkboxes are checked?” The checkboxes know whether or not they are checked, of course, but, the row styles also have to know, the summary text has to know, and each button has to know. Five copies of this information are stored separately all around the HTML, and when it changes in any of those places the JavaScript developer needs to catch that and write imperative code to keep the others in sync.

This is still only a simple example of one small component of a page. If that sounds like a headache, imagine how complex and fragile an application becomes when you need to write the whole thing this way. For many complex modern web applications, it’s not a scalable solution.

Moving towards a single source of truth

Tools, like React, allow us to use JavaScript in a declarative way. Just as HTML is a declarative abstraction wrapped around the web browser’s display instructions, React is a declarative abstraction wrapped around JavaScript.

Remember how HTML let us focus on the structure of a page and not the details of how the browser displays that structure? Well, when we use React, we can focus on the structure again by defining it based on data stored in a single place. When that source of truth changes, React will update the structure of the page for us automatically. It will take care of the imperative steps behind the scenes, just like the web browser does for HTML. (Although React is used as an example here, this concept is not unique to React and is used by other frameworks, such as Vue.)

Let’s go back to our list of checkboxes from the example above. In this case, the truth we care about is simple: which checkboxes are checked? The other details on the page (e.g. what the summary says, the color of the rows, whether or not the buttons are enabled) are effects derived from that same truth. So, why should they need to have their own copy of this information? They should just use the single source of truth for reference, and everything on the page should “just know” which checkboxes are checked and conduct themselves accordingly. You might say that the row elements, summary text, and buttons should all be able to automatically react to a checkbox being checked or unchecked. (See what I did there?)

Tell me what you want (what you really, really want)

In order to implement this page with React, we can replace the list with a few simple declarations of facts:

- There is a list of true/false values called

checkboxValuesthat represents which boxes are checked.- Example:

checkboxValues = [false, false, true, false] - This list represents the truth that we have four checkboxes, and that the third one is checked.

- Example:

- For each value in

checkboxValues, there is a row element which:- has a CSS class called

.selectedif the value is true, and - contains a checkbox, which is checked if the value is true.

- has a CSS class called

- There is a summary text element that contains the text “

{x}of{y}selected” where{x}is the number of true values incheckboxValuesand{y}is the total number of values incheckboxValues. - There is a “Select All” button that is enabled if there are any false values in

checkboxValues. - There is a “Select None” button that is enabled if there are any true values in

checkboxValues. - When a checkbox is clicked, its corresponding value changes in

checkboxValues. - When the “Select All” button is clicked, it sets all values in

checkboxValuesto true. - When the “Select None” button is clicked, it sets all values in

checkboxValuesto false.

You’ll notice that the last three items are still imperative instructions (“When this happens, do that”), but that’s the only imperative code we need to write. It’s three lines of code, and they all update the single source of truth. The rest of those bullets are declarations (“there is a…”) which are now built right into the definition of the page’s structure. In order to do this, we write our elements in a special JavaScript syntax provided by React called JSX, which resembles HTML but can contain JavaScript logic. That gives us the ability to mix logic like “if” and “for each” with the HTML structure, so the structure can be different depending on the contents of checkboxValues at any given time.

Here’s the same shopping list example as above, this time implemented with React:

JSX is definitely weird. When I first encountered it, it just felt wrong. My initial reaction was, “What the heck is this? HTML doesn’t belong in JavaScript!” I wasn’t alone. That said, it’s not HTML, but rather JavaScript dressed up to look like HTML. It is also quite powerful.

Remember that list of 20 imperative instructions above? Now we have three. For the price of defining our HTML inside our JavaScript, the rest of them come for free. React just does them for us whenever checkboxValues changes.

With this code, it is now impossible for the summary to not match the checkboxes, or for the color of a row to be wrong, or for a button to be enabled when it should be disabled. There is an entire category of bugs which are now impossible for us to have in our app: sources of truth being out of sync. Everything flows down from the single source of truth, and we developers can write less code and sleep better at night. Well, JavaScript developers can, at least…

It’s a trade-off

As web applications become more complex, maintaining the classic separation of concerns between HTML and JavaScript comes at an increasingly painful cost. HTML was originally designed for static documents, and in order to add more complex interactive functionality to those documents, imperative JavaScript has to keep track of more things and become more confusing and fragile.

The upside: predictability, reusability and composition

The ability to use a single source of truth is the most important benefit of this pattern, but the trade-off gives us other benefits, too. Defining elements of our page as JavaScript code means that we can turn chunks of it into reusable components, preventing us from copying and pasting the same HTML in multiple places. If we need to change a component, we can make that change in one place and it will update everywhere in our application (or in many applications, if we’re publishing reusable components to other teams).

We can take these simple components and compose them together like LEGO bricks, creating more complex and useful components, without making them too confusing to work with. And if we’re using components built by others, we can easily update them when they release improvements or fix bugs without having to rewrite our code.

The downside: it’s JavaScript all the way down

All of those benefits do come at a cost. There are good reasons people value keeping HTML and JavaScript separate, and to get these other benefits, we need to combine them into one. As I mentioned before, moving away from simple HTML files complicates the workflow of someone who didn’t need to worry about JavaScript before. It may mean that someone who previously could make changes to an application on their own must now learn additional complex skills to maintain that autonomy.

There can also be technical downsides. For example, some tools like linters and parsers expect regular HTML, and some third-party imperative JavaScript plugins can become harder to work with. Also, JavaScript isn’t the best-designed language; it’s just what we happen to have in our web browsers. Newer tools and features are making it better, but it still has some pitfalls you need to learn about before you can be productive with it.

Another potential problem is that when the semantic structure of a page is broken up into abstract components, it can become easy for developers to stop thinking about what actual HTML elements are being generated at the end. Specific HTML tags like

have specific semantic meanings that are lost when using generic tags like

and Use it if it helps you, not because it’s “what’s hot right now”

It’s become a trend for developers to reach for frameworks on every single project. Some people are of the mindset that separating HTML and JavaScript is obsolete, but this isn’t true. For a simple static website that doesn’t need much user interaction, it’s not worth the trouble. The more enthusiastic React fans might disagree with me here, but if all your JavaScript is doing is creating a non-interactive webpage, you shouldn’t be using JavaScript. JavaScript doesn’t load as fast as regular HTML, so if you’re not getting a significant developer experience or code reliability improvement, it’s doing more harm than good.

You also don’t have to build your entire website in React! Or Vue! Or Whatever! A lot of people don’t know this because all the tutorials out there show how to use React for the whole thing. If you only have one little complex widget on an otherwise simple website, you can use React for that one component. You don’t always need to worry about webpack or Redux or Gatsby or any of the other crap people will tell you are “best practices” for your React app.

For a sufficiently complex application, declarative programming is absolutely worth the trouble. It is a game changer that has empowered developers the world over to build amazing, robust and reliable software with confidence and without having to sweat the small stuff. Is React in particular the best possible solution to these problems? No. Will it just be replaced by the next thing? Eventually. But declarative programming is not going anywhere, and the next thing will probably just do it better.

What’s this I’ve heard about CSS-in-JS?

I’m not touching that one.

The post Why JavaScript is Eating HTML appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

The Unseen Performance Costs of Modern CSS-in-JS Libraries

This article is full of a bunch of data from Aggelos Arvanitakis. But lemme just focus on his final bit of advice:

Investigate whether a zero-runtime CSS-in-JS library can work for your project. Sometimes we tend to prefer writing CSS in JS for the DX (developer experience) it offers, without a need to have access to an extended JS API. If you app doesn’t need support for theming and doesn’t make heavy and complex use of the

cssprop, then a zero-runtime CSS-in-JS library might be a good candidate.

“Zero-runtime” meaning you author your styles in a CSS-in-JS syntax, but what is produced is .css files like any other CSS preprocessor would produce. This shifts the tool into a totally different category. It’s a developer tool only, rather than a tool where the user of the website pays the price of using it.

The flagship zero-runtime CSS-in-JS library is Linaria. I think the syntax looks really nice.

import { css } from 'linaria';

import fonts from './fonts';

const header = css`

text-transform: uppercase;

font-family: ${fonts.heading};

`;

<h1 className={header}>Hello world</h1>;I’m also a fan of the just do scoping for me ability that CSS modules brings, which can be done zero-runtime style.

Direct Link to Article — Permalink

The post The Unseen Performance Costs of Modern CSS-in-JS Libraries appeared first on CSS-Tricks.