Django Highlights: Templating Saves Lines (Part 2)

Django Highlights: Templating Saves Lines (Part 2)

Philip Kiely2020-04-02T12:00:00+00:002020-04-02T12:35:28+00:00

Some no-frills approaches to building websites require a developer to write every line of HTML by hand. On the other extreme, commercial no-code site builders create all of the HTML for the user automatically, often at the expense of readability in the resultant code. Templating is around the middle of that spectrum, but closer to hand-written HTML than, say, generating page structure in a single-page application using React or a similar library. This sweet spot on the continuum provides many of the benefits of from-scratch manual HTML (semantic/readable code, full control over page structure, fast page loads) and adds separation of concerns and concision, all at the expense of spending some time writing modified HTML by hand. This article demonstrates using Django templating to write complex pages.

Today’s topic applies beyond the Django framework. Flask (another web framework) and Pelican (a static site generator) are just two of many other Python projects that use the same approach to templating. Jinja2 is the templating engine that all three frameworks use, although you can use a different one by altering the project settings (strictly speaking, Jinja2 is a superset of Django templating). It is a freestanding library that you can incorporate into your own projects even without a framework, so the techniques from this article are broadly useful.

Server-Side Rendering

A template is just an HTML file where the HTML has been extended with additional symbols. Remember what HTML stands for: HyperText Markup Language. Jinja2, our templating language, simply adds to the language with additional meaningful markup symbols. These additional structures are interpreted when the server renders the template to serve a plain HTML page to the user (that is to say, the additional symbols from the templating language don’t make it into the final output).

Server-side rendering is the process of constructing a webpage in response to a request. Django uses server-side rendering to serve HTML pages to the client. At the end of its execution, a view function combines the HTTP request, one or more templates, and optionally data accessed during the function’s execution to construct a single HTML page that it sends as a response to the client. Data goes from the database, through the view, and into the template to make its way to the user. Don’t worry if this abstract explanation doesn’t fully make sense, we’ll turn to a concrete example for the rest of this article.

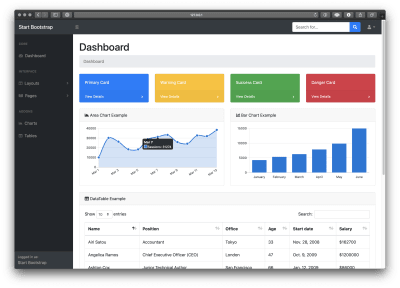

Setting Up

For our example, we’ll take a fairly complex webpage, Start Bootstrap’s admin template, and rewrite the HTML as a Jinja2 template. Note that the MIT-licensed library uses a different templating system (based on JavaScript and Pug) to generate the page you see, but their approach differs substantially from Jinja2-style templating, so this example is more of a reverse-engineering than a translation of their excellent open-source project. To see the webpage we’ll be constructing, you can take a look at Start Bootstrap’s live preview.

I have prepared a sample application for this article. To get the Django project running on your own computer, start your Python 3 virtual environment and then run the following commands:

pip install django

git clone https://github.com/philipkiely/sm_dh_2_dashboard.git

cd sm_dh_2_dashboard

python manage.py migrate

python manage.py createsuperuser

python manage.py loaddata employee_fixture.json

python manage.py runserver

Then, open your web browser and navigate to http://127.0.0.1:8000. You should see the same page as the preview, matching the image below.

Because this tutorial is focused on frontend, the underlying Django app is very simple. This may seem like a lot of configuration for presenting a single webpage, and to be fair it is. However, this much set-up could also support a much more robust application.

Now, we’re ready to walk through the process of turning this 668 line HTML file into a properly architected Django site.

Templating And Inheritance

The first step in refactoring hundreds of lines of HTML into clean code is splitting out elements into their own templates, which Django will compose into a single webpage during the render step.

Take a look in pages/templates. You should see five files:

- base.html, the base template that every webpage will extend. It contains the

with the title, CSS imports, etc. - navbar.html, the HTML for the top navigation bar, a component to be included where necessary.

- footer.html, the code for the page footer, another component to be included where needed.

- sidebar.html, the HTMl for the sidebar, a third component to be included when required.

- index.html, the code unique to the main page. This template extends the base template and includes the three components.

Django assembles these five files like Voltron to render the index page. The keywords that allow this are {% block %}, {% include %}, and {% extend %}. In base.html:

{% block content %}

{% endblock %}These two lines leave space for other templates that extend base.html to insert their own HTML. Note that content is a variable name, you can have multiple blocks with different names in a template, giving flexibility to child templates. We see how to extend this in index.html:

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

<!-- HTML Goes Here -->

{% endblock %}Using the extends keyword with the base template name gives the index page its structure, saving us from copying in the heading (note that the file name is a relative path in double-quoted string form). The index page includes all three components that are common to most pages on the site. We bring in those components with include tags as below:

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% block content %}

{% include "navbar.html" %}

{% include "sidebar.html" %}

<!--Index-Specific HTML-->

{% include "footer.html" %}

<!--More Index-Specific HTML-->

{% endblock %}Overall, this structure provides three key benefits over writing pages individually:

- DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) Code

By factoring out common code into specific files, we can change the code in only one place and reflect those changes across all pages. - Increased Readability

Rather than scrolling through one giant file, you can isolate the specific component you’re interested in. - Separation of Concerns

The code for, say, the sidebar now has to be in one place, there can’t be any roguescripttags floating at the bottom of the code or other intermingling between what should be separate components. Factoring out individual pieces forces this good coding practice.

While we could save even more lines of code by putting the specific components in the base.html template, keeping them separate provides two advantages. The first is that we are able to embed them exactly where they belong in a single block (this is relevant only to the footer.html which goes inside the main div of the content block). The other advantage is that if we were to create a page, say a 404 error page, and we did not want the sidebar or footer, we could leave those out.

These capabilities are par for the course for templating. Now, we turn to powerful tags that we can use in our index.html to provide dynamic features and save hundreds of lines of code.

Two Fundamental Tags

This is very far from an exhaustive list of available tags. The Django documentation on templating provides such an enumeration. For now, we’re focusing on the use cases for two of the most common elements of the templating language. In my own work, I basically only use the for and if tag on a regular basis, although the dozen or more other tags provided to have their own use cases, which I encourage you to review in the template reference.

Before we get to the tags, I want to make a note on syntax. The tag {% foo %} means that “foo” is a function or other capability of the templating system itself, while the tag {{ bar }} means that “bar” is a variable passed into the specific template.

For Loops

In the remaining index.html, the largest section of code by several hundred lines is the table. Instead of this hardcoded table, we can generate the table dynamically from the database. Recall python manage.py loaddata employee_fixture.json from the setup step. That command used a JSON file, called a Django Fixture, to load all 57 employee records into the application’s database. We use the view in views.py to pass this data to the template:

from django.shortcuts import render

from .models import Employee

def index(request):

return render(request, "index.html", {"employees": Employee.objects.all()})The third positional argument to render is a dictionary of data that is made available to the template. We use this data and the for tag to construct the table. Even in the original template that I adapted this webpage from, the table of employees was hard-coded. Our new approach cuts hundreds of lines of repetitive hard-coded table rows. index.html now contains:

{% for employee in employees %}

<trv

<td>{{ employee.name }}</td>

<td>{{ employee.position }}</td>

<td>{{ employee.office }}</td>

<td>{{ employee.age }}</td>

vtd>{{ employee.start_date }}</td>

<td>${{ employee.salary }}</td>

</tr>

{% endfor %}The bigger advantage is that this greatly simplifies the process of updating the table. Rather than having a developer manually edit the HTML to reflect a salary increase or new hire, then push that change into production, any administrator can use the admin panel to make real-time updates (http://127.0.0.1/admin, use the credentials you created with python manage.py createsuperuser to access). This is a benefit of using Django with this rendering engine instead of using it on its own in a static site generator or other templating approach.

If Else

The if tag is an incredibly powerful tag that allows you to evaluate expressions within the template and adjust the HTML accordingly. Lines like {% if 1 == 2 %} are perfectly valid, if a little useless, as they evaluate to the same result every time. Where the if tag shines is when interacting with data passed into the template by the view. Consider the following example from sidebar.html:

<div class="sb-sidenav-footer">

<div class="small">

Logged in as:

</div>

{% if user.is_authenticated %}

{{ user.username }}

{% else %}

Start Bootstrap

{% endif %}

</div>Note that the entire user object is passed into the template by default, without us specifying anything in the view to make that happen. This allows us to access the user’s authentication status (or lack thereof), username, and other features, including following foreign key relationships to access data stored in a user profile or other connected model, all from the HTML file.

You might be concerned that this level of access could pose security risks. However, remember that these templates are for a server-side rendering framework. After constructing the page, the tags have consumed themselves and are replaced with pure HTML. Thus, if an if statement introduces data to a page under some conditions, but the data is not used in a given instance, then that data will not be sent to the client at all, as the if statement is evaluated server-side. This means that a properly constructed template is a very secure method of adding sensitive data to pages without that data leaving the server unless necessary. That said, the use of Django templating does not remove the need to communicate sensitive information in a secure, encrypted manner, it simply means that security checks like user.is_authenticated can safely happen in the HTML as it is processed server-side.

This feature has a number of other use cases. For example, in a general product homepage, you might want to hide the “sign up” and “sign in” buttons and replace them with a “sign out” button for logged-in users. Another common use is to show and hide success or error messages for operations like form submission. Note that generally you would not hide the entire page if the user is not logged in. A better way to change the entire webpage based on the user’s authentication status is to handle it in the appropriate function in views.py.

Filtering

Part of the view’s job is to format data appropriately for the page. To accomplish this, we have a powerful extension to tags: filters. There are many filters available in Django to perform actions like justifying text, formatting dates, and adding numbers. Basically, you can think of a filter as a function that is applied to the variable in a tag. For example, we want our salary numbers to read “$1,200,000” instead of “1200000.” We’ll use a filter to get the job done in index.html:

<td>${{ employee.salary|intcomma }}</td>

The pipe character | is the filter that applies the intcomma command to the employee.salary variable. The “$” character does not come from the template, for an element like that which appears every time, it’s easier to just stick it outside the tag.

Note that intcomma requires us to include {% load humanize %} at the top of our index.html and 'django.contrib.humanize', in our INSTALLED_APPS in settings.py. This is done for you in the provided sample application.

Conclusion

Server-side rendering with the Jinja2 engine provides key tools for creating clean, adaptable, responsive front-end code. Separating pages into files allows for DRY components with flexible composition. Tags provide fundamental capabilities for displaying data passed from the database by view functions. Done right, this approach can increase the speed, SEO capabilities, security, and usability of the site, and is a core aspect of programming in Django and similar frameworks.

If you haven’t done so already, check out the sample application and try adding your own tags and filters using the complete list.

Django Highlights is a series introducing important concepts of web development in Django. Each article is written as a stand-alone guide to a facet of Django development intended to help front-end developers and designers reach a deeper understanding of “the other half” of the code base. These articles are mostly constructed to help you gain an understanding of theory and convention, but contain some code samples, which are written in Django 3.0.