In this episode of the Smashing Podcast, we’re talking about online privacy. What should web developers be doing to make sure the privacy of our users is maintained? I spoke to Laura Kalbag to find out.

Show Notes

Weekly Update

Transcript

Drew McLellan: She’s a designer from the UK, but now based in Ireland, she’s co-founder of the Small Technology Foundation. You’ll often find her talking about rights-respecting design, accessibility and inclusivity, privacy, and web design and development, both on her personal website and with publications such as Smashing magazine. She’s the author of the book Accessibility for Everyone from A Book Apart. And with the Small Technology Foundation, she’s part of the team behind Better Blocker, a tracking blocker tool for Safari on iOS and Mac. So we know she’s an expert in inclusive design and online privacy, but did you know she took Paris Fashion Week by storm wearing a kilt made out of spaghetti. My Smashing friends, please welcome Laura Kalbag.

Laura Kalbag: Hello.

Drew: Hello Laura, how are you?

Laura: I am smashing.

Drew: I wanted to talk to you today about the topic of online privacy and the challenges around being an active participant online without seeding too much of your privacy and personal data to companies who may or may not be trustworthy. This is an area that you think about a lot, isn’t it?

Laura: Yeah. And I don’t just think about the role of us as consumers in that, but also as people who work on the web, our role in actually doing it and how much we’re actually making that a problem for the rest of society as well.

Drew: As a web developer growing up in the ‘90s as I did, for me maintaining an active presence online involved basically building and updating my own website. Essentially, it was distributed technology but it was under my control. And these days it seems like it’s more about posting on centralized commercially operated platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, the obvious ones. That’s a really big shift in how we publish stuff online. Is it a problem?

Laura: Yeah. And I think we have gone far away from those decentralized distributed ways of posting on our own websites. And the problem is that we are essentially posting everything on somebody else’s website. And not only does that mean that we’re subject to their rules, which in some cases is a good thing, you don’t necessarily want to be on a website that is full of spam, full of trolls, full of Nazi content, we don’t want to be experiencing that. But also we have no control over whether we get kicked off, whether they decide to censor us in any way. But also everything underlying on that platform. So whether that platform is knowing where we are at all times because it’s picking up on our location. Whether it is reading our private messages because if it’s not end-to-end encrypted, if we’re sending direct messages to each other, that could be accessed by the company.

Laura: Whether it’s actively, so whether people working there could actually just read your messages. Or passively, where they are just sucking up the stuff from inside your messages and using that to build profiles about you, which they can then use to target you with ads and stuff like that. Or even combine that information with other datasets and sell that on to other people as well.

Drew: It can be quite terrifying, can’t it? Have what you considered to be a private message with somebody on a platform like Facebook, using Facebook Messenger, and find the things you’ve mentioned in a conversation then used to target ads towards you. It’s not something you think you’ve shared but it is something you’ve shared with the platform.

Laura: And I have a classic example of this that happened to me a few years ago. So, I was on Facebook, and my mom had just died, and I was getting ads for funeral directors. And I thought is was really strange because none of my family had said anything on a social media platform at that point, none of my family had said anything on Facebook because we’d agreed that no one wants to find out that kind of thing about a friend or family member via Facebook so we’d not say about it. And then, so I asked my siblings, “Have any of you said anything on Facebook that might cause this strange?” Because I just usually just get ads for make-up, and dresses, and pregnancy tests, and all those fun things they like to target women of a certain age. And my sister got back to me, she said, “Well, yeah, my friend lives in Australia so I sent her a message on Messenger, Facebook Messenger, and told her that our mom had died.”

Laura: And of course Facebook knew that we’re sisters, it has that relationship connection that you can choose to add on there, it could probably guess we were sisters anyway by the locations we’ve been together, the fact that we share a surname. And decided that’s an appropriate ad to put in her feed.

Drew: It’s sobering, isn’t it? To think that technology is making these decisions for us that actually affects people, potentially in this example, in quite a sensitive or vulnerable time.

Laura: Yeah. We say it’s creepy, but a lot of the time people say it’s almost like the microphone on my phone or my laptop was listening to me because I was just having this conversation about this particular product and suddenly it’s appearing in my feed everywhere. And I think what’s actually scary is the fact that most of them don’t have access to your microphone, but it’s the fact that your other behaviors, your search, the fact that it knows who you’re talking to because of your proximity to each other and your location on your devices. It can connect all of those things that we might not connect ourselves together in order to say, maybe they’ll be interested in this product because they’ll probably think you’re talking about it already.

Drew: And of course, it’s not as simple as just rolling back the clock and going back to a time where if you wanted to be online, you had to create your own website because there’s technical barriers to that, there’s cost barriers. And you only need to look at the explosion of things like sharing video online, there’s not an easy way to share a video online in the same way you can just by putting it on YouTube, or uploading it to Facebook, or onto Twitter, there are technical challenges there.

Laura: It’s not fair to blame anyone for it because using the web today and using these platforms today is part of participating in society. You can’t help it if your school has a Facebook group for all the parents. You can’t help it if you have to use a website that, in order to get some vital information. It’s part of our infrastructure now, particularly nowadays when everyone is suddenly relying video calling and things like that so much more. These are our infrastructure, they are as used and as important as our roads, as our utilities, so we need to have them treated accordingly. And we can’t blame people for using them, especially if there aren’t any alternatives that are better.

Drew: When the suggestion is using these big platforms that it’s easy and it’s free, but is it free?

Laura: No, because you’re paying with your personal information. And I hear a lot of developers saying things like, “Oh well, I’m not interesting, I don’t really care, it’s not really a problem for me.” And we have to think about the fact that we’re often in quite a privileged group. What about people that are more vulnerable? We think about people who have parts of their identity that they don’t necessarily want to share publicly, they don’t want to be outed by platforms to their employers, to their government. People who are in domestic abuse situations, we think about people who are scared of their governments and don’t want to spied on. That’s a huge number of people across the world, we can’t just say, “Oh well, it’s fine for me, so it has to be fine for everybody else,” it’s just not fair.

Drew: It doesn’t have to be a very big issue you’re trying to conceal from the world to be worried about what a platform might share about you.

Laura: Yeah. And the whole thing about privacy is that it isn’t about having something to hide, it’s about choosing what you want to share. So you might not feel like you have anything in particular that you want to hide, but it doesn’t necessarily mean you put a camera in your bedroom and broadcast it 24 hours, there’s things we do and don’t want to share.

Drew: Because there are risks as well in sharing social content, things like pictures of family and friends. That we could be sacrificing other peoples privacy without them really being aware, is that a risk?

Laura: Yeah. And I think that that applies to a lot of different things as well. So it’s not just if you’re uploading things of people you know and then they’re being added to facial recognition databases, which is happening quite a lot of the time. These very dodgy databases, they’ll scrape social media sites to make their facial recognition databases. So Clearview is an example of a company that’s done that, they’ve scraped images off Facebook and used those. But also things like email, you might choose… I’m not going to use Gmail because I don’t want Google to have access to everything in my email, which is everything I’ve signed up for, every event I’m attending, all of my personal communication, so I decide not to use it. But if I’m communicating with someone who uses Gmail, well, they’ve made that decision on my behalf, that everything I email them will be shared with Google.

Drew: You say that, often from a privileged position, we think okay, we’re getting all this technology, all these platforms are being given to us for free, we’re not having to pay for it, all we got to do is… We’re giving up a little bit of privacy, but that’s okay, that’s an acceptable trade-off. But is it an acceptable trade-off?

Laura: No. It’s certainly not an acceptable trade-off. But I think it’s also because you don’t necessarily immediately see the harms that are caused by giving these things up. You might feel like you’re in a safe situation today, but you may not be tomorrow. I think a good example is Facebook, they’ve actually got a pattern for approving or disproving loans based on the financial status of your friends on Facebook. So thinking, oh well, if your friend owes lots of money, and a lot of your friends owes lots of money, you’re more likely to be in that same situation as them. So all these systems, all of these algorithms, they are making decisions and influencing our lives and we have no say on them. So it’s not necessarily about what we’re choosing to share and what we’re choosing not to share in terms of something we put in a status, or a photo, or a video, but it’s also about all of this information that is derived about us from our activity on these platforms.

Laura: Things about our locations or whether we have a tendency to be out late at night, the kinds of people that we tend to spend our time with, all of this information can be collected by these platforms too and then they’ll make decisions about us based on that information. And we not only don’t have access to what’s being derived about us, we have no way of seeing it, we have no way of changing it, we have no way of removing it, bar a few things that we could do if we’re in the EU based on GDPR, if you’re in California based on their regulation there that you can go in and ask companies what data they have on you and ask them to delete it. But then what data counts under that situation? Just the data they’ve collected about you? What about the data they’ve derived and created by combining your information with other people’s information and the categories they’ve put you in, things like that. We have no transparency on that information.

Drew: People might say that this is paranoia, this is tinfoil hat stuff. And really all that these companies are doing is collecting data to show us different ads. And okay, there’s the potential for these other things, but they’re not actually doing that. All they’re doing is just tailoring ads to us. Is that the case or is this data actually actively being used in more malicious ways than just showing ads?

Laura: No. We’ve seen in many, many occasions how this information is being used in ways other than just ads. And even if one company decides to just collect it based on ads, they then later might get sold to or acquired by an organization that decides to do something different with that data and that’s parts of the problem with collecting the data at all in the first place. And it’s also a big risk to things like hacking, if you’re creating a big centralized database with people’s information, their phone numbers, their email addresses, even just the most simple stuff, that’s really juicy data for hackers. And that’s why we see massive scale hacks that result in a lot of people’s personal information ending up being publicly available. It’s because a company decided it was a good idea to collect of that information in one place in the first place.

Drew: Are there ways then that we can use these platforms, interact with friends and family that are also on these platforms, Facebook is the obvious example where you might have friends and family all over the world and Facebook is the place where they communicate. Are there ways that you can participate in that and not be giving up privacy or is it just something that if you want to be on that platform, you just have to accept?

Laura: I think there’s different layers, depending on what we would call your threat model is. So depending how vulnerable you are, but also your friends and family, and what your options are. So yeah, the ultimate thing is to not use these platforms at all. But if you do, try to use them more than they use you. So if you have things that you’re communicating one-on-one, don’t use Messenger for that because there are plenty of alternatives for one-on-one direct communication that can be end-to-end encrypted or is private and you don’t have to worry about Facebook listening in on it. And there’s not really much you can do about things like sharing your location data and stuff like that, which is really valuable information. It’s all of your meta information that’s so valuable, it’s not even necessarily the content of what you’re saying, but who you’re with and where you are when you’re saying it. That’s the kind of stuff that’s useful that companies would use to put you in different categories and be able to sell things to you accordingly or group you accordingly.

Laura: So I think we can try to use them as little as possible. I think it’s important to seek alternatives, particularly if you’re a person who is more technically savvy in your group of friends and family, you can always encourage other people to join other things as well to have. So use Wire for messaging, that’s a nice little platform that’s available in lots of places and is private. Or Signal is another option that’s just like WhatsApp but it’s end-to-end encrypted as well. And if you can be that person, I think there’s two points that we have to really forget about. One, is the idea that everyone needs to be on a platform for it to be valuable. The benefit is that everyone’s on Facebook, that’s actually the downside as well, that everyone’s on Facebook. You don’t need everyone you know to suddenly be on the same platform as you. As long as you have those few people you want to communicate with regularly on a better platform, that’s a really good start.

Laura: And the other thing that we need to embrace, we’re not going to find an alternative to a particular platform that does everything that platform does as well. You’re not going to find an alternative to Facebook that does messaging, that has status updates, that has groups, that has events, that has live, that has all of this stuff. Because the reason Facebook can do that is because Facebook is massive, Facebook has these resources, Facebook has a business model that really makes a lot out of all that data and so it’s really beneficial to provide all those services to you. And so we have to change our expectations and maybe be like, “Well okay, what’s the one function I need? To be able to share a photo. Well, let’s find the thing that I can do that will help me just share that photo.” And not be expecting just another great big company to do the right thing for us.

Drew: Is this something that RSS can help us with? I tend to think RSS is the solution to most problems, but I was thinking here if you have a service for photo sharing, and something else for status updates, and something else for all these different things is RSS the solution that brings it all together to create a virtual… That encompasses all these services?

Laura: I’m with you on that for lots of things. I, myself, I’ve built into my own site, I have a section for photos, a section for status updates, as well as my blog and stuff. So that I can allow people to, if they don’t follow me on social media platforms, if I’m posting the same stuff to my site, they can use RSS to access it and they’re not putting themselves at risk. And that’s one of the ways that I see as just a fairly ordinary designer/developer that I can not force other people to use those platforms in order to join in with me. And RSS is really good for that. RSS can have tracking, I think people can do stuff with it, but it’s rare and it’s not the point of it. That’s what I think RSS is a really good standard for.

Drew: As a web developer, I’m aware when I’m building sites that I’m frequently being required to add JavaScript from Google for things like analytics or ads, and from Facebook for like and share actions, and all that sort of thing, and from various other places, Twitter, and you name it. Are those something that we need to worry about in terms of developers or as users of the web? That there’s this code executing that it’s origin is on google.com or facebook.com?

Laura: Yes. Absolutely. I think Google is a good example here of things like web fonts and libraries and stuff like that. So people are encouraged to use them because they’re told well, it’s going to very performant, it’s on Google servers, Google will grab it from the closest part of the world, you’ll have a brilliant site just by using, say a font off Google rather than embedding it, self-hosting it on your own site. There’s a reason why Google offers up all of those fonts for free and it’s not out of the goodness of their Googley little hearts, it is because they get something out of it. And what they get is, they get access to your visitors on your website when you include their script on your website. So I think it’s not just something we should be worried about as developers, I think that it’s our responsibility to know what our site is doing and know what a third party script is doing or could do, because they could change it and you don’t necessarily have control over that as well. Know what their privacy policies are and things like that before we use them.

Laura: And ideally, don’t use them at all. If we can self-host things, self-host things, a lot of the time it’s easier. If we don’t need to provide a login with Google or Facebook, don’t do it. I think we can be the gatekeepers in this situation. We as the people who have the knowledge and the skills in this area, we can be the ones that can go back to our bosses or our managers and say, “Look, we can provide this login with Facebook or we could build our own login, it will be private, it would be safer. Yeah, it might take a little bit more work but actually we’ll be able to instill more trust in what we’re building because we don’t have that association with Facebook.” Because what we’re seeing now, over time, is that even mainstream media is starting to catch up with the downsides of Facebook, and Google, and these other organizations.

Laura: And so we end up being guilty by association even if we’re just trying to make the user experience easier by adding a login where someone doesn’t have to create a new username and password. And so I think we really do need to take that responsibility and a lot of it is about valuing people’s rights and respecting their rights and their privacy over our own convenience. Because of course it’s going to be much quicker just to add that script to the page, just to add another package in without investigating what it actually does. We’re giving up a lot when we do that and I think that we need to take responsibility not to.

Drew: As web developers are there other things that we should be looking out for when it comes to protecting the privacy of our own customers in the things that we build?

Laura: We shouldn’t be collecting data at all. And I think most of the time, you can avoid it. Analytics is one of my biggest bugbears because I think that a lot of people get all these analytics scripts, all these scripts that can see what people are doing on your website and give you insights and things like that, but I don’t think we use them particularly well. I think we use them to confirm our own assumptions and all we’re being taught about is what is already on our site. It’s not telling us anything that research and actually talking to people who use our websites… We could really benefit more from that than just looking at some numbers go up and down, and guessing what the effect of that is or why it’s happening. So I think that we need to be more cautious around anything that we’re putting on our sites and anything that we’re collecting. And I think nowadays we’re also looking at regulatory and legal risks as well when we’re starting to collect people’s data.

Laura: Because when we look at things like the GDPR, we’re very restricted in what we are allowed to collect and the reasons why we’re allowed to collect it. And that’s why we’re getting all of these consent notifications and things like that coming up now. Because companies have to have your explicit consent for collecting any data that is not associated with vital function for the website. So if you’re using something like a login, you don’t need to get permission to store someone’s email and password for a login because that is implied by logging in, you need that. But things like analytics and stuff like that, you actually need to get explicit consent in order to be able to spy on the people visiting the website. So this is why we see all of these consent boxes, this is why we should actually be including them on our websites if we’re using analytics and other tools that are collecting data that aren’t vital to the functioning of the page.

Drew: I think about some of even just the side projects and things that I’ve launched, that just almost as a matter of routine I’ve put Google analytics on there. I think, “Oh, I need to track how many people are visiting.” And then I either never look at it or I only look at it to gain an understanding of the same things that I could’ve just got from server logs like we used to do in the old days, just by crunching over their web access logs.

Laura: Exactly. And yet Google is sitting there going, “Thank you very much.” Because you’ve instilled another input for them on the website. And I think once you start thinking about it, once you adjust your brain to taking this other way of looking at it, it’s much easier to start seeing the vulnerabilities. But we do have to train ourselves to think in that way, to think about how can we harm people with what we’re building, who could lose out from this, and try to build things that are a bit more considerate of people.

Drew: There’s an example, actually, that I can think of where Google analytics itself was used to breach somebody’s privacy. And that was the author of Belle de Jour, The Secret Diary of a Call Girl, who was a London call girl who kept a blog for years and it was all completely anonymous. And she diarized her daily life. And it was incredibly successful, and it became a book, and a TV series, and what have you. She was intending to be completely anonymous, but she was eventually found out. Her identity was revealed because she used the same Google analytics tracking user id on her personal blog where she was her professional self and on the call girl blog as well. And that’s how she was identified, just-

Laura: So she did it to herself in that way as well.

Drew: She did it to herself. Yeah. She leaked personal data there that she didn’t mean to leak. She didn’t even know it was personal data, I suspect. There are so many implications that you just don’t think of. And so I think it pays to start thinking of it.

Laura: Yeah. And not doing things because you feel that that’s what we always did, and that’s what we always do, or that’s what this other organization that I admire, they do it, so I should, I think. And a lot of the time it is about being a bit more restrictive and maybe not jumping on the bandwagon of I’m going to use this service like everybody else is. And stopping, reading their privacy policy, which is not something I recommend doing for fun, because it’s really tedious, and I have to do a lot of it when I’m looking into trackers for Better. But you can see a lot of red flags if you read privacy policies. You see the kinds of language that means that they’re trying to make it free and easy for them to do whatever they want with your information. And there’s a reason why I say to designers and developers, if you’re making your own projects, don’t just copy the privacy policy from somebody else. Because you might be opening yourself up to more issues and you might actually be making yourself look suspicious.

Laura: It’s much better to be transparent and clear about what you’re doing, everything doesn’t need to be written in legal ease in order for you to be clear about what you’re doing with people’s information.

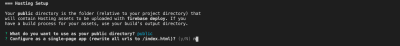

Drew: So, in almost anything, people say that the solution to it is to use the JAMstack. Is the JAMstack a solution, is it a good answer, is it going to help us out of accidentally breaching the privacy of our customers?

Laura: There’s a lot of stuff I like about the JAMstack stuff, but I would say I like the “JMstack”, because it’s the APIs bit that worries me. Because if we’re taking control over our own sites, we’re building static sites, and we’re generating it all on our machines, and we’re not using servers, and that’s great that we’ve taken away a lot potential issues there. But then if we’re adding back in all of the third party functionality using APIs, we may as well be adding script tags to our pages all over again. We may as well have it on somebody else’s platform. Because we’re losing that control again. Because every time we’re adding something from a third party, we’re losing control over a little bit of our site. So I think that a lot of static site generators and things like that have a lot of value, but we still need to be cautious.

Laura: And I think one of the reasons why we love the jam stack stuff because again, it’s allowed us to knock up a site really quickly, deploy it really quickly, have a development environment set up really quickly, and we’re valuing again, our developer experience over that of the people that are using the websites.

Drew: So I guess the key there is to just be hyperaware of what every API you’re using is doing. What data you could be sending to them, what their individual privacy policies are.

Laura: Yeah. And I think we have to be cautious about being loyal to companies. We might have people that we are friends with and think are great and things like that, that are working for these companies. We might that they are producing some good work, they’re doing good blogs, they’re introducing some interesting new technologies into the world. But at the end of the day, businesses are businesses. And they all have business models. And we have to know what are their business models. How are they making their money? Who is behind the money? Because a lot of venture capital backed organizations end up having to deal in personal data, and profiling, and things like that, because it’s an easy way to make money. And it is hard to build a sustainable business on technology, particularly if you’re not selling a physical product, it’s really hard to make a business sustainable. And if an organization has taken a huge amount of money and they’re paying a huge amount of employees, they’ve got to make some money back somehow.

Laura: And that’s what we’re seeing now is, so many businesses doing what Shoshana Zuboff refers to as surveillance capitalism, tracking people, profiling them, and monetizing that information because it’s the easiest way to make money on the web. And I think that the rest of us have to try to resist it because it can be very tempting to jump in and do what everyone else is doing and make big money, and make a big name. But I think that we’re realizing too slowly the impact that that has on the rest of our society. The fact that Cambridge Analytica only came about because Facebook was collecting massive amounts of people’s information and Cambridge Analytica was just using that information in order to target people with, essentially, propaganda in order to make referendums and elections of their way. And that’s terrifying, that’s a really scary effect that’s come out of what you might think is an innocuous little banner ad.

Drew: Professionally, many people are transitioning into building client sites or helping their clients to build their own sites on platforms like Squarespace and that sort of thing, online site builders where sites are then completely hosted on that service. Is that an area that they should also be worried about in terms of privacy?

Laura: Yeah. Because you’re very much subject to the privacy policies of those platforms. And while a lot of them are paid platforms, so just because it’s a platform doesn’t necessarily mean that they are tracking you. But the inverse is also true, just because you’re paying for it, doesn’t mean they’re not tracking you. I’d use Spotify as an example of this. People pay Spotify a lot of money for their accounts. And Spotify does that brilliant thing where it shows off how much it’s tracking you by telling people all of this incredible information about them on a yearly basis, and giving them playlists for their moods, and things like that. And then you realize, oh, actually, Spotify knows what my mood is because I’m listening to a playlist that’s made for this mood that I’m in. And Spotify is with me when I’m exercising. And Spotify knows when I’m working. And Spotify knows when I’m trying to sleep. And whatever other playlists you’ve set up for it, whatever other activities you’ve done.

Laura: So I think we just have to look at everything that a business is doing in order to work out whether it’s a threat to us and really treat everything as though it could possibly cause harm to us, and use it carefully.

Drew: You’ve got a fantastic personal website where you collate all the things that you’re working on and things that you share socially. I see that your site is built using Site.js. What’s that?

Laura: Yes. So it’s something that we’ve been building. So what we do at the Small Technology Foundation, or what we did when we were called Ind.ie, which was the UK version of the Small Technology Foundation, is that we’re tying to work on how do we help in this situation. How do we help in a world where technology is not respecting people’s rights? And we’re a couple of designers and developers, so what is our skills? And the way we see it is we have to do a few different things. We have to first of all, prevent some of the worst harms if we can. And one of the ways we do that is having a tracker blocker, so it’s something that blocks trackers on the web, with their browser. And another thing we do is, we try to help inform things like regulation, and we campaign for better regulation and well informed regulation that is not encouraging authoritarian governments and is trying to restrict businesses from collecting people’s personal information.

Laura: And the other thing we can do is, we can try to build alternatives. Because one of the biggest problems with technology and with the web today is that there’s not actually much choice when you want to build something. A lot of things are built in the same way. And we’ve been looking at different ways of doing this for quite a few years now. And the idea behind Site.js is to make it really easy to build and deploy a personal website that is secure, has the all the HTTPS stuff going on and everything, really, really, easily. So it’s something that really benefits the developer experience, but doesn’t threaten the visitor’s experience at the same time. So it’s something that is also going to keep being rights respecting, that you have full ownership and control over as the developer of your own personal website as well. And so that’s what Site.js does.

Laura: So we’re just working on ways for people to build personal websites with the idea that in the future, hopefully those websites will also be able to communicate easily with each other. So you could use them to communicate with each other and it’s all in your own space as well.

Drew: You’ve put a lot of your expertise in this area to use with Better Blocker. You must see some fairly wild things going on there as you’re updating it and…

Laura: Yeah. You can always tell when I’m working on Better because that’s when my tweets get particularly angry and cross, because it makes me so irritated when I see what’s going on. And it also really annoys me because I spend a lot of time looking at websites, and working out what the scripts are doing, and what happens when something is blocked. One of the things that really annoys me is how developers don’t have fallbacks in their code. And so the amount of times that if you block something, for example, I block an analytics script, and if you block an analytics script, all the links stop working on the webpage, then you’re probably not using the web properly if you need JavaScript to use a link. And so I wish that developers bear that in mind, especially when they think about maybe removing these scripts from their sites. But the stuff I see is they…

Laura: I’ve seen, like The Sun tabloid newspaper, everybody hates it, it’s awful. They have about 30 different analytics scripts on every page load. And to some degree I wonder whether performance would be such a hot topic in the industry if we weren’t all sticking so much junk on our webpages all the time. Because, actually, you look at a website that doesn’t have a bunch of third party tracking scripts on, tends to load quite quickly. Because you’ve got to do a huge amount to make a webpage heavy if you haven’t got all of that stuff as well.

Drew: So is it a good idea for people who build for the web to be running things like tracker blockers and ad blockers or might it change our experience of the web and cause problems from a developer point of view?

Laura: I think in the same way that we test things across different browsers and we might have a browser that we use for our own consumer style, I hate the word consumer, use, just our own personal use, like our shopping and our social stuff, and things like that. And we wouldn’t only test webpages in that browser, we test webpages in as many browsers can get our hands on because that’s what makes us good developers. And I think the same should be for if you’re using a tracker blocker or an ad blocker in your day-to-day, then yeah, you should try it without as well. Like I keep Google Chrome on my computer for browser testing, but you can be sure that I will not be using that browser for any of my personal stuff, ever, it’s horrible. So yeah, you’ve got to be aware of what’s going in the world around you as part of your responsibility as a developer.

Drew: It’s almost just like another browser combination, isn’t it? To be aware of the configurations that the audience your site or your product might have and then testing with those configurations to find any problems.

Laura: Yeah. And also developing more robust ways of writing your code, so that your code can work without certain scripts and things like that. So not everything is hinging off one particular script unless it is absolutely necessary. Things completely fall apart when people are using third party CDNs, for example. I think that’s a really interesting thing that so many people decided to use a third party CDN, but you have very little control over it’s uptime and stuff like that. And if you block the third party CDN, what happens? Suddenly you have no images, no content, no videos, or do you have no functionality because all of your functional JavaScript is coming from a third party CND?

Drew: As a web developer or designer, if I’d not really thought about privacy concerns about the sites I’m producing up until this point, if I wanted to make a start, what should be the first thing that I do to look at the potential things I’m exposing my customers to?

Laura: I’d review one of your existing pages or one of your existing sites. And you can take it on a component by component basis even. I think any small step is better than no step. And it’s the same way you’d approach learning anything new. It’s the same way I think about accessibility as well. Is you start by, okay, what is one thing I can take away? What is one thing I can change that will make a difference? And then you start building up that way of thinking, that way of looking at how you’re doing your work. And eventually that will build up into being much more well informed about things.

Drew: So I’ve been learning a lot about online privacy. What have you been learning about lately?

Laura: One of the things I’ve been learning about is Hugo, which is a static site generator that is written using Go. And I use it for my personal site already, but right now for Site.js, I’ve been writing a starter blog theme so that people could just set up a site really easily and don’t necessarily have to know a lot about Hugo. Because Hugo is interesting, it’s very fast, but the templating is quite tricky and the documentation is not the most accessible. And so I’m trying to work my way through that to understand it better, which I think I finally got over the initial hurdle. Where I understand what I’m doing now and I can make it better. But it’s hard learning these stuff, isn’t it?

Drew: It really is.

Laura: It reminds you how inadequate you are sometimes.

Drew: If you, dear listener, would like to hear more from Laura, you can find her on the web at laurakalbag.com and Small Technology Foundation at small-tech.org. Thanks for joining us today, Laura. Do you any parting words?

Laura: I’d say, I think we should always just be examining what we’re doing and our responsibility in the work that we do. And what can we do that can make things better for people? And what we can do to make things slightly less bad for people as well.

(il)