In this episode, we ask what qualities are required to introduce change in large organizations, how to convince management to do the right thing, and how to ship a billion-dollar idea. Vitaly talks to expert Paul Boag to find out.

Show Notes

Weekly Update

Transcript

Vitaly Friedman: He’s a user experience consultant conversion rate optimization specialist, and all-around expert in digital transformation from Dorset in southwest England. He helps savvy marketers, product owners, and UX advocates make the case that a usable, accessible, and people-first experience and are not reading this and seeing this. He’s the best part of business success. In fact, he’s worked in digital for 25 years, and according to his Twitter profile, he’s a very grumpy old man off the web. Apparently, he also is an author of six books on topics such as conversion rate optimization and digital and transformation. And he provides coaching, training, and consultancy for digital strategy. So we know he’s an expert in digital transformation, conversion rate optimization, and UX, and all that stuff. But did you know that he spends every Saturday evening drinking tea and chatting with his Cheshire cat called Frankie.

Paul: Lies.

Vitaly: Mass smashing friends, please welcome Paul Boag, and hello, Paul, how are you feeling today?

Paul: Not bad. All things considered. That’s the official British answer to how are you. There’s a really funny comedian called Bill Bailey who talks about that. He says about how Americans, when they’re asked how they are, they’re awesome; everything’s awesome. It’s an awesome day. And I’m having an awesome time, while the British say, well, not bad. That’s as good as it ever gets; it means all things considered.

Vitaly: Means that it’s okay. Yeah. Okay.

Paul: Yeah. Yeah, no, that’s, that’s a good thing. Not bad is good.

Vitaly: Right. Right. Well, it’s wonderful to have you back here. I mean, we go way back, and it’s wonderful to see you in person as well. Although I have to admit, in a very different setting, with a very great background in the back and no fancy lamps, no fancy lighting, no even fancy microphones, what’s going on with your life, Paul. I was told that you’re now not at home. And this is kind of going to stay this way for a while.

Paul: Yeah. So it’s your fault because I saw your jet-setting lifestyle for so many years where you were traveling around continually. And I thought I wanted that, but being me, being old and not quite as adventurous as you going from Airbnb to Airbnb, we bought an RV out in the states. And so we are now traveling around. We’re basically trailer trash now. We’re traveling around the states, sleeping in car parks, and just visiting the various places around the states. It’s good; actually, it’s very enjoyable, but yes, it means I don’t have my fancy podcast set up, and I just look like a disembodied head amongst the brown background.

Vitaly: No, that’s not that bad actually. So I should give you credit for that. You blend in well. Talking about blending in, I would say it’s interesting because always now, when I think of you, I always think about all the things that you’ve been doing all these years. And it feels like you had so many different hats. At one point, you would be doing mostly UX, and you would be doing digital strategy, and then you were coding websites back in the day as well, right?

Paul: Yeah. Well, we all did back in the day.

Vitaly: Yeah, sure. And also, we worked in agencies, and being a big part of an agency and not having your own big career as a digital UX consultant. So I’m wondering, there might be some people here listening, thinking about, who are just starting out their career, and UX is a good thing to kind of dive into. Is there anything Paul that you are now looking back think, okay, I wish that when I was starting out, when was it like 20, 25 years ago, I wish I had known X or Y, what would be those things?

Paul: Yeah. I mean, it was 27 years ago now, which is terrifying. Yeah, it’s a question that I often get asked. I think the main thing that I would say to myself, and of course, it was a very different world back then, and the web was very different. So people often ask me, oh, what advice can you give someone starting in their UX career today? Well, none because I started mine so long ago that it was totally different. But in terms of what I would tell myself, which is what you asked, I think I tell myself to focus on the soft skills. Don’t get caught up on the latest tool or the latest design technique, or whatever. Those things come and go, but interacting with people, being persuasive, presenting your ideas well, and not being a complete idiot to work with.

Paul: Those are the kinds of skills that really last, so. And we’re really bad at teaching those. Take Smashing Magazine, and this isn’t a criticism of Smashing Magazine, because everybody has got this problem. You’ll find hundreds of posts about design techniques, development techniques, all of those kinds of things, but you don’t find as many posts about how to survive a meeting with your boss or how to pitch the design-in, or how to review somebody else’s code without coming across as an asshole. That those are the kinds of skills that I think are in short supply.

Vitaly: Well, maybe we should change that. I mean, I heard that you have a bit of time while you’re traveling some places. Would you like to write a few articles maybe that would be just on that topic?

Paul: Well, to be honest, yeah. I mean, to be honest, a lot of the articles I have written for you have been around that kind of thing.

Vitaly: True. That’s right.

Paul: Because I do tend to write that kind of stuff because I think it’s important. I mean, the favorite article I ever wrote for you was one about mental health, wasn’t it? “You’re not a machine” and “you’re not alone”, which it’s still one of my favorite articles I’ve ever written because I think it was a very important article to write, but it had nothing to do with design or development.

Vitaly: Well, I remember another article that you wrote a while back that got quite a bit of… How to put it? It was argued. Many people were arguing if this is a good way of kind of explaining things or not because I remember vividly you publishing that article about SEO, right? Yeah. Do you want to share that story?

Paul: Not really. No. Because I don’t want to drag it all up again. No. So, I wrote an article saying that, yeah, SEO, I can’t even remember really what it said.

Vitaly: I remember.

Paul: But basically, I was rude about SEO, wasn’t I? but that was a long time ago, to be honest. And SEO has come a long way since then. It was back in the day where SEO was a lot of smoke and mirrors, and oh, we’re going to spam links and all of that kind of stuff/ now, of course, because Google’s algorithm has matured, most of SEO is basically good content, which is great. That’s the way SEO should be. And actually, that was what I implied in the article back then, that you should just focus on creating great content. That was part of what I said as I remember. Spend your money on content, not on SEO consultants.

Vitaly: Yeah, yeah. Yeah. Pretty much sort of plenty of SEO consultants that came your way decided to argue with you in the comments. I remember that vividly. Not only in the comments, I’m sure.

Paul: But it was really good, you see. See, I think sometimes it’s really difficult because we’ve lost the ability to disagree without it escalating. I mean, that did escalate to some degree. There were a lot of people that strongly disagreed with me, but I had some amazing conversations at the back of that. And I actually posted a follow-up post on my own site, which basically said, “You’ve educated me.” The view that I shared of SEO on Smashing Magazine was even then a little bit out of date, and that SEO was already transitioning away from what I described as being towards more being content-focused. And so, it was a really educational process to me, and I think it was a very worthwhile conversation. But these days, it’s like that would’ve exploded up into quite a violent and obnoxious discussion. And it did to some degree even then, but not as bad as I think it would’ve done today.

Vitaly: That’s about right. That’s about right. Well, you mentioned that you’ve been in this industry for 27 years now. That’s a lot of time, of course. That makes me wonder, though. So, you’ve been doing this, maybe some kind of similar work, for such a long time. So have we actually managed to sort out these general misunderstandings about the role of UX and what UX means and how to use UX, and how to transform organizations? Because it seems like we still keep running in circles, having the same conversations. So did we fail at kind of doing the good UX education work out there? Or where do you see the state of things now working with companies and organizations small and large?

Paul: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, things have certainly progressed; they’re much better than they were. So I think most organizations now recognize the value of UX, which is a huge step forward. They didn’t always. I think the many larger organizations, UX is taken more seriously. And it does have that “seat at the table” to some degree. I think, however, there is still a lot of confusion about what UX is and what it isn’t. I think it’s still used interchangeably with UI. So UX, UI designer. While in my mind, those are very different roles. So yeah, I mean, we’re making progress, but like anything, these things take time, don’t they? Cultural change is always difficult. And when you’re talking about an entirely new discipline and integrating that into existing organizations, that doesn’t happen overnight, and we’re still only a quarter of a century old, which is barely out of our teens.

Vitaly: That’s right. That’s about right. Well, now that you’re talking about those large organizations/companies because you’re spending quite a bit of time working with companies on digital transformation. And I even heard that you wrote some books about this.

Paul: I did, which are published by Smashing Magazine of the Excellent Publishing House.

Vitaly: Oh, that’s very kind of you, but this was not supposed to be a promo at all, actually. But I’m actually quite wondering because I’m working on my own in some kind of large rooted organization, and they are bringing along this notion of let’s establish a UX culture. This sounds very foreign. Something doesn’t feel almost alienating to some people like, oh, you want to do this now? We’ve always been working differently. So why should we do that now? Why should we change that now? So what would be then your starting point if you want to start moving an organization again, of any size, really towards something that would be a little bit more user-centric? They have their own, of course, business goals. They have their own KPI. They have their own old way of thinking. And in my experience, changing the way people work is hard. It sometimes takes not even years, like multiple years; it’s really, really difficult. So, how would you start moving the needle?

Paul: Yeah. The bigger the organization, the longer it takes to turn. I mean, there are different ways of doing it, top-down or bottom-up. If you do it top-down, then you are basically targeting senior management initially. And sometimes, someone in senior management gets it, and then you can start chipping away from that angle. But most of the time, it has to come from the grassroots. And really, I think of it as a political movement. Let’s take changing policy towards the environment, right? If you just go in and you write your MP, you’re not going to get anywhere by yourself. Okay? The way that you get large-scale change like that is your band together with other people that feel the same. You make a lot of noise, and you get the attention of those people in power.

Paul: And fundamentally, it’s the same when you’re trying to change an organization, you have to find allies. You have to find other people in the organization that has got the same desire to be more user-centric. Now they might not know the term UX, but they might. Marketers, for example. UX people are very rude to marketers, but ultimately they want to achieve the same thing because they want customers to be happy; because if customers are happy, they repeat buy. They recommend you to other people, et cetera. So you could go to those people, and you start creating an informal group of people that share your views on UX. And then you start to mobilize just like a political movement would do. Write yourself a manifesto, right? What do you stand for? What do you want? What change do you actually want to see? Very specifically.

Paul: Then do you start propaganda, basically. You start doing lunchtime sessions and sharing UX best practices. You send emails around. You get in guest speakers. You make a noise. I’ve run internal conferences within organizations. I’ve started newsletters and internal blogs; you run a marketing campaign, promoting user experience best practices. And that’s how you do it. And you begin to build momentum over time and only go to senior management when you have got sufficient momentum that they can’t ignore you. But you’re right. That takes time. Takes time to build that kind of culture.

Vitaly: Yeah. So the interesting part for me is really that very often it feels like you really have to be so well prepared for that meeting with senior management.

Paul: Yeah.

Vitaly: Sometimes it feels like you have like 20 minutes shot. This is the window that you get. And if you can convince them, that’s the only chance you get because nobody’s going to be talking to you ever again.

Paul: Then you’re doing it wrong, right? I’ve walked into meetings like that. I’ve been in meetings like that, but I already know the result by the time I stepped through the door, right? A meeting like that has got to basically be a rubber stamp by that stage. You have got to have spoken individually to each of the people in that meeting before the meeting, you have to need to have won them over beforehand. And a lot of that is about, let’s say… It’s a couple of mistakes people make; first of all, they go into meetings like that, and they go, well, no one think of the user. And nobody cares about the user other than you. So that’s mistake number one. And then-

Vitaly: That’s a little bit disappointing.

Paul: Yeah. But it’s true. Because we’re all inherently selfish, and we’re no different, right? If somebody from the compliance team said to you, will you not think about our legal obligations, right? Are you telling me you would really give a shit? No, of course, you wouldn’t. Right? Because you’re selfish. You care about users because you’re a user experience designer. So we all are selfish. We all think about our own individual areas. So, that’s one thing, don’t talk about users. You’re wasting your time. The second thing with those kinds of winning over senior management is that you got to not ask for too much, right? So, for example, I don’t know, let’s say you’re Disney, right? And you’re a little group of Disney, and you’ve got this amazing idea of you to want to create magic bands with RDF chips in them that could do all these incredible things.

Paul: But you know it’s going to cost a billion dollars to renovate all of the hotels, all of the theme parks, all the rest of it. You don’t go into senior management and say, can I have a billion dollars? Because they’re going to say no, no matter what it is that you say. What you do is you go in and say, can I build a prototype, a proof of concept, right? For a much smaller fee using a backlog, right? And this is exactly what Disney did. So, reduce your ask, go for little steps. Slimy tactics to move towards your idea. And then in terms of the, not talking about the user, instead what you do is you go to each of those stakeholders and to the finance person, you say, well, if we implemented this magic band, yes, there’s going to be a big upfront cost.

Paul: But our ongoing operational costs are going to go down as a result because the finance person likes that, right? And then you talk to the marketing person, and you say, oh, can you imagine how excited kids are going to be to get their band? And how people are going to photograph it, and they’re going to share their band if we could personalize the band, so they’re different. They’re going to love that.

Paul: And then you talk to the operational director, and you say, oh, well, people won’t have to have money, so the number of transactions that need to be processed will go down. And so we could be more efficient in the way we work. So I’m taking the same idea, and instead of talking about the user experience, I’m tailoring it to each of those different people that I’m speaking to. So when I walk in the room, they’re already all convinced, right? Otherwise, you are wasting your time because you walk into the room, you give a pitch, and you can’t tailor it to the individual person. You’ve not got enough time to convince them. So you’ve got to do it before you get there.

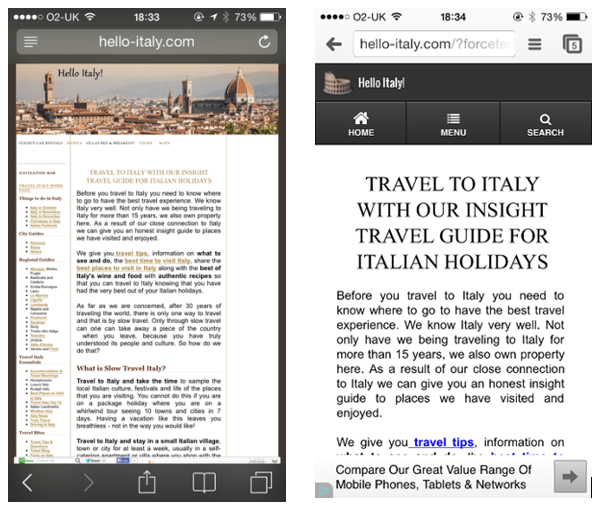

Vitaly: Okay. Well, I think we should be speaking a bit more in the nearest future as well, but maybe actually looking into some more of the kind of navigation search kind of problems that often show up on websites. People don’t find what they want to find. People can’t accomplish stuff that they want to accomplish. And let’s imagine just taking an example, you have a huge site, which has dozens and dozens of subsites, different departments, owning different sites. It’s all very messy. Some of them are a kind of legacy. Some are just really poorly designed, and all those things, plenty of content duplication, ambiguous labels, just all the best things kind of put together, right? What would be the kind of your process to actually just deal with it in a complex organization that has just literally hundreds, maybe even thousands of people involved that is willing to actually get better in terms of UX?

Paul: Well, it depends how willing they are.

Vitaly: Well, they hired you. They hire the best person in town. So they pretty much are.

Paul: No, no, no, no. Do you honestly think that’s the case? Lots of people think they’re willing until they realize what is actually involved. In a situation like that, Okay. I was going to make a flipping comment. I won’t make a flipping comment. What would I really do? Okay. In a situation like that, I think the first thing I would want to do is audit everything, so. And I don’t mean an in-depth audit because there’ll be too much to do a proper content audit. But I literally would want a list of all of the sites. And I would want an owner for every single one of those, who owns it, right? And who is maintaining it. I’d also probably want very top-level analytics on it. How much traffic is each of those sites is getting and a sense of when the site is last updated, right?

Paul: And the reason that I want all of that is because normally, in the vast majority of situations, there will be a load of stuff that could be just cold, right? That nobody really owns, that hasn’t been updated for the longest time, that has got hardly any traffic going to it. So the aim would be to viciously cold back everything that was there. And the logic is very simple, right? The logic basically boils down to… For a long time, there’s been a perception that it’s like a brochure. You publish it, and you’re done, which we now know is not an option. That you get rocked, redundant and trivial content. And so any web service, any website, needs to be maintained over time, which means it needs an active owner and active budget, regular reviews, et cetera.

Paul: So when you’ve got hundreds and hundreds of websites, potentially thousands of websites, you’ve got one of two options, haven’t you? One is that you hire enough staff to actively manage every single one of those websites, right? Which you end up with hundreds and hundreds of people, basically, which is totally unfeasible. So you pitch that first. And of course, everybody says no, because that’s completely unrealistic. There’s no way that you can justify that. So that leaves option B, which is to reduce your footprint, your digital footprint down to a manageable level, right? And so that means culling anything that can’t be actively managed and maintained across the organization.

Vitaly: But Paul, that means deleting and archiving stuff. That’s scary. Who wants that in a large organization? Who knows, maybe we’ll delete something important, maybe we will not be able to find something important. Who even knows all the dependencies on all those things?

Paul: Yeah. Yeah. Yes. So you’re not going to delete anything. Because A, why? The web is cheap. Having content online is cheap, but what we need to do is we need to archive it. And by that, we need to remove it from navigation. We need to remove it from search .it can still be Googled, and any internal links that go to it will still work. But then, at the top of the page, we need to add a banner or notification that basically says this page is no longer being maintained. It was last updated on this date, right? So, that can deal with anybody’s fears that content is going to just disappear and it’s going to break stuff. Then there’ll be other content that you have to have online for compliance purposes that nobody ever looks at, but it has to be there. Fine.

Paul: Then with that kind of content, what you’re going to do is you’re going to remove it from navigation. You may potentially remove it from the internal search, but you still have a direct link that you can share as you need to. So there are lots of ways. Everybody thinks that every page that we have online has to be treated equally and has to be treated in the same way. There has to be part of the navigation. It has to be part of the search. In reality, probably most stuff doesn’t. A lot of stuff is just legacy or standalone content, or that could just be directly linked, that could be handed out as a URL, et cetera. And then, of course, that simplifies your navigation down. It simplifies your search down. It means that people can indeed find the needle in the haystack, so. Because you’ve just suddenly made that who stack a lot smaller. So, yeah, I mean, it’s really about stripping back to something that’s actually manageable and maintainable by the organization.

Vitaly: I can always hear people screaming in the back of the room, screaming and asking about things that were related to what you mentioned earlier, all those practical tips about how to convince management about anything. I think, at some point, you were even thinking about writing an article, how to convince… Or maybe it was my title that [inaudible 00:25:44].

Paul: You suggested I wrote a book on it.

Vitaly: Yeah.

Paul: And I said, “I’ll write an article for now.” And I’ve actually written the article for you, but I just don’t think you’ve published it yet. So it’s your problem, mate.

Vitaly: Oh, okay. Well, I’ll have to look into that, but maybe kind of bringing this up again, it’s always the same story. I think it’s always very useful to get insight from experienced people like yourself about how would you even deal with situations where you get difficult clients, where you get scope changes that are coming in late, where you have situations when you just have a really poor specification, you have communication problems, all those things, right? This is pretty much in every single project that’s going to be appearing in one way or the other. So what would be your good strategy to deal with on the one hand with managers, right? And on the other hand with clients?

Paul: I mean, I do a whole day workshop on this. I’ve literally just done a workshop on that for front-end masters. So yeah, it’s a huge subject that I think… What would be my top tip out of that?

Vitaly: You surely have some topics.

Paul: Yeah. Yeah. The trouble is a lot of it is kind of interlinked things. So, for example, it’s about how you set up a project in the first place and manage expectations out of the gate in terms of whose role is what. And let’s take, for example, scope creep, right? With scope creep, there’s nothing wrong with scope creep, right? As you go through a project, right? You learn things, don’t you? You do user testing, hopefully. You do user research, hopefully. You just have ideas when you’ve seen the prototype that hasn’t occurred to you. So what happens out of those things? You have ideas, you learn new things, you learn improvements, and you want to improve them. So actually, scope creep is good, right? The only problem with scope creep is we insist on having projects with fixed budgets, with fixed timelines, and fixed deliverables, right?

Paul: If we get rid of that idea, then suddenly scope creep is fine, but that’s complicated to do, that opens up another can of worms, right? So one of the things that you might want to do is don’t do these big website projects, right? So occasionally, I get asked to redesign a website. I don’t tend to do a lot of that work these days. But often, if I’m asked to do that, I’m asked to kind of oversee the process. And the first thing I say is, I am not going to do a project that is an end-to-end project, right? From initial user research through to delivery and post-launch optimization. I’m not doing that as a single project. That is a big mistake. Instead, I’m going to run a series of smaller projects. I’m going to do a discovery phase, right?

Paul: Which is going to clearly identify user needs, the competition, the constraints, everything like that. And then that is going to inform me, giving you a quote and a timeline for a prototyping phase where I create a visualization of it. And I test that and that visualization and that prototype, that’s going to allow me then to quote for the build phase, right? And I could give you a price hourly because each phase informs the next. So how you structure projects makes a big difference. And then, of course, that means that between each of those stages, between discovery and prototype, between prototype and build, you could change the scope all you want because it’s another project. So things like that make a big difference as well. So, yeah.

Vitaly: Yeah, but what if you’re working, let’s say, you have this big procurement processes and all those big companies and tenders and all those things where you kind of need to know upfront. I’m guessing looking at your face right now that you are going to say, just don’t do them. But I’m wondering if this is the answer that we should be getting to?

Paul: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I don’t do them. It’s the honest answer because I’m lazy. And any time there’s a procurement team involved, which requires a fixed price and fixed scope, immediately that’s a warning flag for me that it’s going to be a nightmare project. So I’m just too lazy to deal with it. But I understand that I’m in quite a privileged position. What I did do when I ran Head Scape with projects like that, and my preferred approach there is to, yeah, I’ll give them a ballpark for the whole thing, right? I will quote them for the whole thing. But in my tender, I will say that this is an estimate only. And I will introduce the idea of breaking the project down and doing it in different ways. Just because you receive a brief asking for a certain set of deliverables in a certain thing doesn’t mean you have to give them that, right? It’s okay to say, hang on a minute. I don’t think you’re doing this in the smartest way, right? And that there is an alternative, better way of doing it.

Paul: Now, one of two things will happen in a situation like that. Either they’ll dismiss you out of hand, right? In which case, you really don’t want to work on that project, right? Because it will be a nightmare from beginning to end, the expectations will be unrealistic. It will be challenging. There will be problems with scope creep and all those different areas that we’ve just talked about. They will happen. There will be no way around them, right? So that would be a huge warning sign.

Paul: Or they go, oh, these people are suggesting something different. Oh, that’s interesting. And they’ll actually like the fact that you’ve challenged their brief, and suddenly all of your competition that has just blindly followed the procurement rules and done what they were told to do suddenly look less proactive. They look less like they care about the project and that they want the best for the project. So actually, it’s a really good way of differentiating yourself to actually turn around and say, well, here’s something that kind of gives you a sense of the overall budget, but this is how you really should work it. And that ultimately it’ll work out cheaper that way. Because obviously, the overall budget, I have to add a load of guesses in there and a load of contingency in case my guesses are bad.

Vitaly: Yeah. Yeah. So I also see some agencies or companies using value-based pricing, where they actually go in and think about the impact that they can make in an organization and then kind of price based on that. What’s your take on this?

Paul: It’s BS. There you go. Here we go. This could be SEO, the SEO article all over again.

Vitaly: I’m very much excited about what’s coming up next year listeners, please pay attention now. Bookmark this spot in the recording.

Paul: Oh, people are going to hate me for this. Jonathan’s start is a great… I think it’s Jonathan’s Start. My brain is just shut down. He’s a really great guy who pushes value-based pricing a lot. I’m cynical about it. Some people seem to manage to get it to work, and good on them. And well done them, but it feels like a fantasy to me, value-based pricing. I understand, theoretically makes a lot of sense. If I’m going to earn a company a million, then it’s perfectly reasonable for me to take 10% of that $100,000, even though it’s five grand worth of my time, right? That’s perfectly reasonable. Don’t disagree with the principle. It’s the reality of it that is difficult for two reasons. One is that in a vast number of projects, depending on the type of projects you do, that can be extremely hard to prove, to get real numbers, right?

Paul: So unless it’s an eCommerce site or something like that, then actually it’s pretty hard to get a solid estimate on how much potential you could make. Secondly, you are giving no guarantees that you will get that level of return. And you can’t make those guarantees because there are so many variables involved. When you are quoting at the beginning of the project, you don’t know what constraints may exist that would limit what you can do. You don’t know what the client might say they want or don’t want. They might come up with stuff that’s a bad idea. There are so many things you do not know that there is nowhere on earth you can be confident you can generate that degree of return, right? And so how then, can you say, I want this percentage of that number. So I think, in principle, it’s great, and it sounds wonderful in practice, but it rarely works.

Vitaly: So Paul then can you hear the voices from the back again saying, but Paul, but Paul, but we are UX practitioners. If you look at the number of job applications all around on UX, it’s tons of openings. So because he was speaking about millions, how do you then become a millionaire by being a UX designer? It doesn’t work. Well, the reason I’m bringing up this question is because a good friend of mine told me once many, many, many years ago, he’s kind of more my mentor. And he told me, “Well, you never become a millionaire by just working 24/7 or kind of having a full-time job alone. You really need to think about passive income. You really have to think about how do you invest money? And you cannot just make a lot of money by working nonstop. That’s just not going to work.” So how then do we become a millionaire, as you expect?

Paul: Why are you asking me? I’m not a millionaire?

Vitaly: Why not? Well, you do have a wonderful, fancy chocolate background in there.

Paul: exactly. Well, this looks really high quality, doesn’t it? You can tell that I’m in a quality vehicle at the moment. First of all, I would challenge why do you want to become a millionaire? And this is really interesting. Take my dad, for example, right? My dad is a worldwide photographer. They have barely any money ever, right? They earn below the national average of the UK. Okay? Yet they travel around the world, right? They go on multiple cruises every year. They go all of these amazing places on somebody else’s dime, right? Because he’s a wildlife photographer. And he lectures on cruise liners and stuff like that. So money is only a way of enabling you to do what it is that you want to do. So the question then becomes what you want to do. And because I do a lot of mentorship of agency owners, right? And agency owners, a lot of them start going on about passive income and stuff like that. And don’t get me wrong. I have passive income. I get passive income for the courses that I run. I would say the royalties from the books, but how little that actually is, but I do get-

Vitaly: Let’s not put it out there.

Paul: Well, you don’t get rich writing books. Everybody knows that. That’s not why you write them. I mean, unless you write Harry Potter or whatever, so. So, but I do have passive income, but not an enormous amount, but I live the life. I want to live. I go where I want to go; I do what I want to do. So the question then is not, how do I become a millionaire, but how do I get the lifestyle that I want, right? And that’s a very different question. And there are different ways of doing it. And passive income might be a part of it.

Paul: In other words, an exit strategy where you sell on your business, whatever that is. And then you can retire early. I take the approach of I’ve designed a business where I have to work four hours a day, right? So, and that is achievable as a UX designer or a UX, or you can get your rate to a point where you can get away with working four hours a day, take over a good income, and spend the rest of your time enjoying yourself. So, I don’t think the answer is just to become a millionaire. I think the answer is to get the lifestyle you want. That’s my opinion anyway. Unless, of course, your lifestyle is I want a yacht. In which case, you do need to be a millionaire.

Vitaly: Well, yeah, but just because you’re working four hours a day, we cannot afford you anymore. Because you’re getting really, really expensive, no, I’m just kidding at this point.

Paul: Yeah. No, no, I am very expensive, right? I’ll be upfront with you. I will charge anywhere between 195 and 165 pounds an hour, right? That is my rate, depending on the number of hours that you buy. And I can maintain a charge-out rate at that level because I’ve built a reputation that means that demand for my services outstrips my ability to supply that. So basically, I could charge and weed out people that can’t afford me unless I really fancy the project. That’s enough. This is how you should price projects, right? And this comes from Mike Coos. Do you know Mike Coos? Yeah. He’s an amazing, amazing designer amazing from Australia. And he told me this once, he said… when he comes to pricing, this is how he prices. He says to himself, “How much would they have to pay me to make me want to do this enthusiastically, right.” And I think that’s a great way of pricing. Okay? Because then you work on the stuff that you really, really want to work on, right? That you really enjoy. And because you charge that at a lower rate and then the stuff that you don’t want to do, you charge at a higher rate, which subsidizes the stuff at a lower rate, so.

Vitaly: Yeah, that makes sense. But what would you suggest then to people who maybe don’t have that much experience and they kind of have to compete on the market, and the market is quite saturated? I mean, if you’re a UX expert, that’s great. That works, but still, you go to there are plenty of platforms which provide services for like $30, $50, $80.

Paul: Yeah. Don’t play the game.

Vitaly: Yeah. So what would be the strategy for kind of pricing there?

Paul: So, I work with a lot of agencies that are kind working on these platforms like Fiver and Upwork and stuff like that. And those platforms are universally, without exception, price orientated, right? So you are always going to be stuck at the bottom of the market, and you’re always going to be competing on price at that point. And also, you’re competing against free stuff. You’re competing against creating a page that you can use a template from on Square Space; it’s a losing battle. So you’ve got to move out of the bottom of the market. So how do you move out of the bottom of the market? Where you start to build your own audience, rather than relying on the audience that’s provided by these marketplaces. And I’ve got a course on this called Finding Clients where essentially you need to decide, okay, I want to target a specific sector, because most freelancer agencies, their marketing approaches are terrible because they’ve got no training in it.

Paul: They don’t know how to do it. Nobody’s ever taught them how to do this kind of stuff. And so they throw out the old blog post, and they redesign their website for the 20th time. And they put out a few social updates, and they call that marketing well, that’s not going to win you any new clients. You need a strategy for targeting a particular sector, getting into that sector, and building relationships with that sector. So you become the go-to person for that sector. And once you are the go-to person, once you are the person that everybody goes to higher education, you must go to Paul for that; once you get to that point because you are specializing, then you could push your rates up. And also, you are targeting a sector that isn’t just going, oh, I need a cheap web designer. Now I know I’ve skipped over a lot of detail about doing all of that, but you know, we haven’t got that long, but.

Vitaly: We’ll have another session on just that I’m sure, sometimes soon in the future, I think.

Paul: Sure.

Vitaly: So maybe just one final question to wrap this kind of slowly wrap this up. I think just two weeks ago, I received an email from somebody who just, again, working maybe I think three or four years spent in the industry, and what they were asking is how do I negotiate my salary? So I’m working, let’s say, in a product team, or I’m working in an agency, and it feels like you are hired for the position, and you’re kind of stuck. So, the inflation is now through the roof, and it doesn’t seem like everybody’s going to get any increase in the foreseeable future also because the company isn’t doing that well. So at which point and how, what would be kind of strategic advice from your end to say, this is how you do it in order to increase your salary, at least, get a stronger position in the company, maybe instead of salary have more ownership or anything like that over time. What’s the right way of doing it?

Paul: I don’t really know. Sorry. That’s a really bad answer to your last question.

Vitaly: No, that’s an honest answer.

Paul: But the truth is the reason I don’t know is the last time I worked for a company was in 2001. So yeah. So it’s not an area I work in. Of course, I was an employer for a long length of time. And I could tell you what an employer’s big fears are, which is that you leave and so our desire is to maintain our staff because getting the new staff is really, really expensive. So I think if you are getting dissatisfied with your salary, probably an honest conversation with your boss and say, look, I want to be completely upfront with you, all right? I’m getting to the point where my cost at home because of inflation and all the rest of it is getting high. I’m going to need to start looking for another job, I’m afraid, right?

Paul: And instead of me taking lots of half-day sick and that kind of stuff, which is so obvious, I thought I’m going to be upfront with you and tell you instead. And if I get offered another job, I will come and talk to you first; if you want to match the salary, then we can certainly have that conversation because I don’t want to leave here. But this is the situation that I’m in. And it might be that is enough for them to want to nip that problem in the bud. And they’ll give you an increase there; if not, follow through on that, look for other jobs, find other positions. And if you do get an offer, go back to them. So sometimes, that’s the only way of doing it. It’s just honesty about your situation. Because most employers, in my experience at least, they’re not out to screw you over. They’ve got their own targets and things that they’re worrying about their own, budget-free constraints and that kind of stuff. And so honesty is always the best policy. Isn’t it really?

Vitaly: Yeah. That sounds about right. Well, maybe the final one, then. So Paul, is there the universal wish you would be writing a book about all those things combined and again, the management and the growth, and I don’t know what else. Do you have time doing it, don’t you?

Paul: No, I don’t have time on my hand. I will write another book. I will inevitably write another book eventually. It’s obviously quite a big-time commitment to write a book. I don’t think it could be about…

Vitaly: Is it? I think for you, it’s easy peasy. You just go ahead and say, okay, I can commit to the next three months. And then I get a chapter once a week. That’s much what it was like last time around.

Paul: Yeah. I mean, I can write a first draft in about a month of solid effort. Yeah. But I don’t earn any money in that month, so. And you got to keep that in mind as well.

Vitaly: I mean, we do pay some pennies,

Paul: But it doesn’t cover my charge out rate. Let’s put it like that, which we’ve already established is unrealistically high, so. But of course, it’s completely worth it for me to write a book because it kind of generates new business and stuff like that. But it does mean I’m in an interesting position. Let’s be honest about these things, right? I write books about subjects that I want to work on more right. So when I wanted to do digital transformation, I wrote Digital Adaptation. When I wanted to do more organizational user experience cultural change, I wrote User Experience Revolution. When I wanted to do conversion rate optimization, I wrote Click. That is simply how it works. And every time, without fail, it shifts people’s perception of what I’m an expert at.

Paul: And I win work in that, right? So it’s a really good marketing strategy, but there’s the problem. Literally, if I write a book on soft skills or I write a book on winning clients or whatever, what work does that bring me? See, that’s the interesting one, isn’t it? And that’s where you have to think ahead with these things. And what I was saying earlier about your marketing approach needs to be strategic. Yeah, perhaps it would get me more work with agency mentorship, freelance mentorship, and stuff like that. But that’s not a big earner compared to working for a multinational company.

Vitaly: Well, I know I have another title. No, no, no, no, no. I have another title. I would love you to write a book about something like, I don’t know, establishing processes or working in large enterprise organizations.

Paul: Yeah. See, now that one, that’s got a lot more potential, a lot more legs for it in terms of running my own business.

Vitaly: I think so too. So when should we sign the contract then?

Paul: No time soon, I’m afraid. I’m overjoyed in my life at the moment, so.

Vitaly: Okay. Well, that sounds about good. That’s good enough for me, but I’m not going to let it go, Paul. I’m just saying, so I’m going to send you a few messages back and forth.

Paul: Yeah. I’m feeling really bad about this interview. I feel like all I’ve come across is this really callous person that won’t do anything unless I’m paid; there’s other money to do it.

Vitaly: No, I don’t think it comes across this way at all. I think when I look at the articles and every now and again, when I Google anything really, I will be stumbling upon one of the articles that you have written over all this, what, 200 years?

Paul: 200. Yeah. Coming up to 200, right?

Vitaly: Yeah. That’s pretty impressive. So this in mind, I mean, I have no doubt that you do a lot of things also just because you honestly believe in that. If you, dear listener, would like to hear more from Paul, you can also find him on Twitter, where he’s at Paul Boag, and on his website, which is, surprise, surprise, Boagworld.com. His books, all the books that he’s so kindly mentioned in the last five minutes also available, of course, from Smashing Magazine. So you can also find them and read them. And if you want Paul to write more books, send him messages. Actually, he’ll appreciate that. Right from that end. Thanks so much for joining us today. Paul, do you have any parting words of wisdom with the wonderful people listening to us now?

Paul: I’ve always got the same one, which is a success is going from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm, which is a Winston Churchill quote. And when it talks about whether you’re talking about getting a pay rise, whether you’re talking about changing the culture in your organization, or whether you’re talking about getting a project over the line, success is going from failure to failure without any loss of enthusiasm. So just keep chipping away, and you’ll get there.