Designing And Building A Progressive Web Application Without A Framework (Part 3)

Designing And Building A Progressive Web Application Without A Framework (Part 3)

Ben Frain2019-07-30T14:00:00+02:002019-07-31T07:36:14+00:00

Back in the first part of this series, we explained why this project came to be. Namely a desire to learn how a small web application could be made in vanilla JavaScript and to get a non-designing developer working his design chops a little.

In part two we took some basic initial designs and got things up and running with some tooling and technology choices. We covered how and why parts of the design changed and the ramifications of those changes.

In this final part, we will cover turning a basic web application into a Progressive Web Application (PWA) and ‘shipping’ the application before looking at the most valuable lessons learned by making the simple web application In/Out:

- The enormous value of JavaScript array methods;

- Debugging;

- When you are the only developer, you are the other developer;

- Design is development;

- Ongoing maintenance and security issues;

- Working on side projects without losing your mind, motivation or both;

- Shipping some product beats shipping no product.

So, before looking at lessons learned, let’s look at how you turn a basic web application written in HTML, CSS, and JavaScript into a Progressive Web Application (PWA).

In terms of total time spent on making this little web-application, I’d guestimate it was likely around two to three weeks. However, as it was done in snatched 30-60 minute chunks in the evenings it actually took around a year from the first commit to when I uploaded what I consider the ‘1.0′ version in August 2018. As I’d got the app ‘feature complete’, or more simply speaking, at a stage I was happy with, I anticipated a large final push. You see, I had done nothing towards making the application into a Progressive Web Application. Turns out, this was actually the easiest part of the whole process.

Making A Progressive Web Application

The good news is that when it comes to turning a little JavaScript-powered app into a ‘Progressive Web App’ there are heaps of tools to make life easy. If you cast your mind back to part one of this series, you’ll remember that to be a Progressive Web App means meeting a set of criteria.

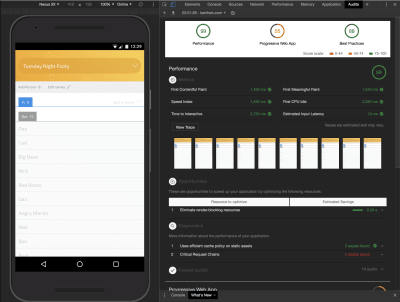

To get a handle on how your web-application measures up, your first stop should probably be the Lighthouse tools of Google Chrome. You can find the Progressive Web App audit under the ‘Audits’ tab.

This is what Lighthouse told me when I first ran In/Out through it.

At the outset In/Out was only getting a score of 55?100 for a Progressive Web App. However, I took it from there to 100?100 in well under an hour!

The expediency in improving that score was little to do with my ability. It was simply because Lighthouse told me exactly what was needed to be done!

Some examples of requisite steps: include a manifest.json file (essentially a JSON file providing metadata about the app), add a whole slew of meta tags in the head, switch out images that were inlined in the CSS for standard URL referenced images, and add a bunch of home screen images.

Making a number of home screen images, creating a manifest file and adding a bunch of meta tags might seem like a lot to do in under an hour but there are wonderful web applications to help you build web applications. How nice is that! I used https://app-manifest.firebaseapp.com. Feed it some data about your application and your logo, hit submit and it furnishes you with a zip file containing everything you need! From there on, it’s just copy-and-paste time.

Things I’d put off for some time due to lack of knowledge, like a Service Worker, were also added fairly easily thanks to numerous blog posts and sites dedicated to service workers like https://serviceworke.rs. With a service worker in place it meant the app could work offline, a requisite feature of a Progressive Web Application.

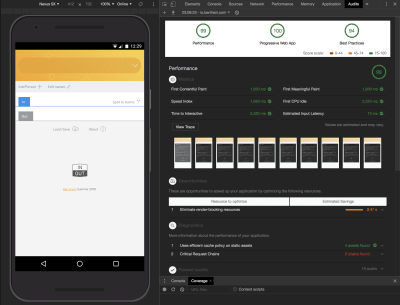

Whilst not strictly related to making the application a PWA, the ‘coverage’ tab of the Chrome Dev Tools were also very useful. After so much sporadic iteration on the design and code over months, it was useful to get a clear indication of where there was redundant code. I found a few old functions littering the codebase that I’d simply forgotten about!

In short order, having worked through the Lighthouse audit recommendations I felt like the teacher’s pet:

The reality is that taking the application and making it a Progressive Web Application was actually incredibly straightforward.

With that final piece of development concluded I uploaded the little application to a sub-domain of my website and that was it.

Retrospective

Months have passed since parking up development my little web application.

I’ve used the application casually in the months since. The reality is much of the team sports organization I do still happens via text message. The application is, however, definitely easier than writing down who is in and out than finding a scrap of paper every game night.

So, the truth is that it’s hardly an indispensable service. Nor does it set any bars for development or design. I couldn’t tell you I’m 100% happy with it either. I just got to a point I was happy to abandon it.

But that was never the point of the exercise. I took a lot from the experience. What follows are what I consider the most important takeaways.

Design Is Development

At the outset, I didn’t value design enough. I started this project believing that my time spent sketching with a pad and pen or in the Sketch application, was time that could be better spent with coding. However, it turns that when I went straight to code, I was often just being a busy fool. Exploring concepts first at the lowest possible fidelity, saved far more time in the long run.

There were numerous occasions at the beginning where hours were spent getting something working in code only to realize that it was fundamentally flawed from a user experience point of view.

My opinion now is that paper and pencil are the finest planning, design and coding tools. Every significant problem faced was principally solved with paper and a pencil; the text editor merely a means of executing the solution. Without something making sense on paper, it stands no chance of working in code.

The next thing I learned to appreciate, and I don’t know why it took so long to figure out, is that design is iterative. I’d sub-consciously bought into the myth of a Designer with a capital “D”. Someone flouncing around, holding their mechanical pencil up at straight edges, waxing lyrical about typefaces and sipping on a flat white (with soya milk, obviously) before casually birthing fully formed visual perfection into the world.

This, not unlike the notion of the ‘genius’ programmer, is a myth. If you’re new to design but trying your hand, I’d suggest you don’t get hung up on the first idea that piques your excitement. It’s so cheap to try variations so embrace that possibility. None of the things I like about the design of In/Out were there in the first designs.

I believe it was the novelist, Michael Crichton, who coined the maxim, “Books are not written — they’re rewritten”. Accept that every creative process is essentially the same. Be aware that trusting the process lessens the anxiety and practice will refine your aesthetic understanding and judgment.

You Are The Other Dev On Your Project

I’m not sure if this is particular to projects that only get worked on sporadically but I made the following foolhardy assumption:

“I don’t need to document any of this because it’s just me, and obviously I will understand it because I wrote it.”

Nothing could be further from the truth!

There were evenings when, for the 30 minutes I had to work on the project, I did nothing more than try to understand a function I had written six months ago. The main reasons code re-orientation took so long was a lack of quality comments and poorly named variables and function arguments.

I’m very diligent in commenting code in my day job, always conscientious that someone else might need to make sense of what I’m writing. However, in this instance, I was that someone else. Do you really think you will remember how the block of code works you wrote in six months time? You won’t. Trust me on this, take some time out and comment that thing up!

I’ve since read a blog post entitled, Your syntax highlighter is wrong on the subject of the importance of comments. The basic premise being that syntax highlighters shouldn’t fade out the comments, they should be the most important thing. I’m inclined to agree and if I don’t find a code editor theme soon that scratches that itch I may have to adapt one to that end myself!

Debugging

When you hit bugs and you have written all the code, it’s not unfair to suggest the error is likely originating between the keyboard and chair. However, before assuming that, I would suggest you test even your most basic assumptions. For example, I remember taking in excess of two hours to fix a problem I had assumed was due to my code; in iOS I just couldn’t get my input box to accept text entry. I don’t remember why it hadn’t stopped me before but I do remember my frustration with the issue.

Turns out it was due to a, still yet to be fixed, bug in Safari. Turns out that in Safari if you have:

* {

user-select: none;

}

In your style sheet, input boxes won’t take any input. You can work around this with:

* {

user-select: none;

}

input[type] {

user-select: text;

}

Which is the approach I take in my “App Reset” CSS reset. However, the really frustrating part of this was I had learned this already and subsequently forgotten it. When I finally got around to checking the WebKit bug tracking whilst troubleshooting the issue, I found I had written a workaround in the bug report thread more than a year ago complete with reduction!

Want To Build With Data? Learn JavaScript Array Methods

Perhaps the single biggest advance my JavaScript skills took by undergoing this app-building exercise was getting familiar with JavaScript Array methods. I now use them daily for all my iteration and data manipulation needs. I cannot emphasize enough how useful methods like map(), filter(), every(), findIndex(), find() and reduce() are. You can solve virtually any data problem with them. If you don’t already have them in your arsenal, bookmark https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Array now and dig in as soon as you are able. My own run-down of my favored array methods is documented here.

ES6 has introduced other time savers for manipulating arrays, such as Set, Rest and Spread. Indulge me while I share one example; there used to be a bunch of faff if you wanted to remove duplicates from even a simple flat array. Not anymore.

Consider this simple example of an Array with the duplicate entry, “Mr Pink”:

let myArray = [

"Mr Orange",

"Mr Pink",

"Mr Brown",

"Mr White",

"Mr Blue",

"Mr Pink"

];

To get rid of the duplicates with ES6 JavaScript you can now just do:

let deDuped = [...new Set(myArray)]; // deDuped logs ["Mr Orange", "Mr Pink", "Mr Brown", "Mr White", "Mr Blue"]

Something that used to require hand-rolling a solution or reaching for a library is now baked into the language. Admittedly, on such as short Array that may not sound like such a big deal but imagine how much time that saves when looking at arrays with hundreds of entries and duplicates.

Maintenance And Security

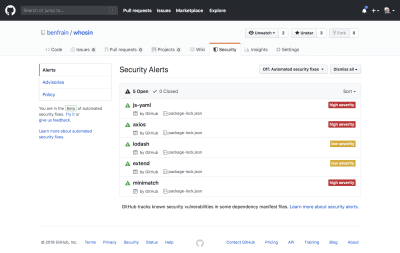

Anything you build that makes any use of NPM, even if just for build tools, carries the possibility of being vulnerable to security issues. GitHub does a good job of keeping you aware of potential problems but there is still some burden of maintenance.

For something that is a mere side-project, this can be a bit of a pain in the months and years that follow active development.

The reality is that every time you update dependencies to fix a security issue, you introduce the possibility of breaking your build.

For months, my package.json looked like this:

{

"dependencies": {

"gulp": "^3.9.1",

"postcss": "^6.0.22",

"postcss-assets": "^5.0.0"

},

"name": "In Out",

"version": "1.0.0",

"description": "simple utility to see who's in and who's out",

"main": "index.js",

"author": "Ben Frain",

"license": "MIT",

"devDependencies": {

"autoprefixer": "^8.5.1",

"browser-sync": "^2.24.6",

"cssnano": "^4.0.4",

"del": "^3.0.0",

"gulp-htmlmin": "^4.0.0",

"gulp-postcss": "^7.0.1",

"gulp-sourcemaps": "^2.6.4",

"gulp-typescript": "^4.0.2",

"gulp-uglify": "^3.0.1",

"postcss-color-function": "^4.0.1",

"postcss-import": "^11.1.0",

"postcss-mixins": "^6.2.0",

"postcss-nested": "^3.0.0",

"postcss-simple-vars": "^4.1.0",

"typescript": "^2.8.3"

}

}

And by June 2019, I was getting these warnings from GitHub:

None were related to plugins I was using directly, they were all sub-dependencies of the build tools I had used. Such is the double-edged sword of JavaScript packages. In terms of the app itself, there was no problem with In/Out; that wasn’t using any of the project dependencies. But as the code was on GitHub, I felt duty-bound to try and fix things up.

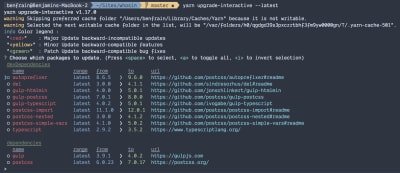

It’s possible to update packages manually, with a few choice changes to the package.json. However, both Yarn and NPM have their own update commands. I opted to run yarn upgrade-interactive which gives you a simple means to update things from the terminal.

Seems easy enough, there’s even a little colored key to tell you which updates are most important.

You can add the --latest flag to update to the very latest major version of the dependencies, rather than just the latest patched version. In for a penny…

Trouble is, things move fast in the JavaScript package world, so updating a few packages to the latest version and then attempting a build resulted in this:

As such, I rolled back my package.json file and tried again this time without the --latest flag. That solved my security issues. Not the most fun I’ve had on a Monday evening though I’ll be honest.

That touches on an important part of any side project. Being realistic with your expectations.

Side Projects

I don’t know if you are the same but I’ve found that a giddy optimism and excitement makes me start projects and if anything does, embarrassment and guilt makes me finish them.

It would be a lie to say the experience of making this tiny application in my spare time was fun-filled. There were occasions I wish I’d never opened my mouth about it to anyone. But now it is done I am 100% convinced it was worth the time invested.

That said, it’s possible to mitigate frustration with such a side project by being realistic about how long it will take to understand and solve the problems you face. Only have 30 mins a night, a few nights a week? You can still complete a side project; just don’t be disgruntled if your pace feels glacial. If things can’t enjoy your full attention be prepared for a slower and steadier pace than you are perhaps used to. That’s true, whether it’s coding, completing a course, learning to juggle or writing a series of articles of why it took so long to write a small web application!

Simple Goal Setting

You don’t need a fancy process for goal setting. But it might help to break things down into small/short tasks. Things as simple as ‘write CSS for drop-down menu’ are perfectly achievable in a limited space of time. Whereas ‘research and implement a design pattern for state management’ is probably not. Break things down. Then, just like Lego, the tiny pieces go together.

Thinking about this process as chipping away at the larger problem, I’m reminded of the famous Bill Gates quote:

“Most people overestimate what they can do in one year and underestimate what they can do in ten years.”

This from a man that’s helping to eradicate Polio. Bill knows his stuff. Listen to Bill y’all.

Shipping Something Is Better Than Shipping Nothing

Before ‘shipping’ this web application, I reviewed the code and was thoroughly disheartened.

Although I had set out on this journey from a point of complete naivety and inexperience, I had made some decent choices when it came to how I might architect (if you’ll forgive so grand a term) the code. I’d researched and implemented a design pattern and enjoyed everything that pattern had to offer. Sadly, as I got more desperate to conclude the project, I failed to maintain discipline. The code as it stands is a real hodge-bodge of approaches and rife with inefficiencies.

In the months since I’ve come to realize that those shortcomings don’t really matter. Not really.

I’m a fan of this quote from Helmuth von Moltke.

“No plan of operations extends with any certainty beyond the first contact with the main hostile force.”

That’s been paraphrased as:

“No plan survives first contact with the enemy”.

Perhaps we can boil it down further and simply go with “shit happens”?

I can surmise my coming to terms with what shipped via the following analogy.

If a friend announced they were going to try and run their first marathon, them getting over the finish line would be all that mattered — I wouldn’t be berating them on their finishing time.

I didn’t set out to write the best web application. The remit I set myself was simply to design and make one.

More specifically, from a development perspective, I wanted to learn the fundamentals of how a web application was constructed. From a design point of view, I wanted to try and work through some (albeit simple) design problems for myself. Making this little application met those challenges and then some. The JavaScript for the entire application was just 5KB (gzipped). A small file size I would struggle to get to with any framework. Except maybe Svelte.

If you are setting yourself a challenge of this nature, and expect at some point to ‘ship’ something, write down at the outset why you are doing it. Keep those reasons at the forefront of your mind and be guided by them. Everything is ultimately some sort of compromise. Don’t let lofty ideals paralyze you from finishing what you set out to do.

Summary

Overall, as it comes up to a year since I have worked on In/Out, my feelings fall broadly into three areas: things I regretted, things I would like to improve/fix and future possibilities.

Things I Regretted

As already alluded to, I was disappointed I hadn’t stuck to what I considered a more elegant method of changing state for the application and rendering it to the DOM. The observer pattern, as discussed in the second part of this series, which solved so many problems in a predictable manner was ultimately cast aside as ‘shipping’ the project became a priority.

I was embarrassed by my code at first but in the following months, I have grown more philosophical. If I hadn’t used more pedestrian techniques later on, there is a very real possibility the project would never have concluded. Getting something out into the world that needs improving still feels better than it never being birthed into the world at all.

Improving In/Out

Beyond choosing semantic markup, I’d made no affordances for accessibility. When I built In/Out I was confident with standard web page accessibility but not sufficiently knowledgeable to tackle an application. I’ve done far more work/research in that area now, so I’d enjoy taking the time to do a decent job of making this application more accessible.

The implementation of the revised design of ‘Add Person’ functionality was rushed. It’s not a disaster, just a bit rougher than I would like. It would be nice to make that slicker.

I also made no consideration for larger screens. It would be interesting to consider the design challenges of making it work at larger sizes, beyond simply making it a tube of content.

Possibilities

Using localStorage worked for my simplistic needs but it would be nice to have a ‘proper’ data store so it wasn’t necessary to worry about backing up the data. Adding log-in capability would also open up the possibility of sharing the game organization with another individual. Or maybe every player could just mark whether they were playing themselves? It’s amazing how many avenues to explore you can envisage from such simple and humble beginnings.

SwiftUI for iOS app development is also intriguing. For someone who has only ever worked with web languages, at first glance, SwiftUI looks like something I’m now emboldened to try. I’d likely try rebuilding In/Out with SwiftUI — just to have something specific to build and compare the development experience and results.

And so, it’s time to wrap things up and give you the TL;DR version of all this.

If you want to learn how something works on the web, I’d suggest skipping the abstractions. Ditch the frameworks, whether that’s CSS or JavaScript until you really understand what they are dong for you.

Design is iterative, embrace that process.

Solve problems in the lowest fidelity medium at your disposal. Don’t go to code if you can test the idea in Sketch. Don’t draw it in Sketch if you can use pen and paper. Write out logic first. Then write it in code.

Be realistic but never despondent. Developing a habit of chipping away at something for as little as 30 minutes a day can get results. That fact is true whatever form your quest takes.